Bichromate gum technique

The bichromate gum technique was invented to

reproduce works without having to engrave them. Engraving was

the only reproduction technique that existed until the middle

of the 19th century (see for example of the very beautiful burin

engraving by J. B.

Danguin (1823-1894) of

the portrait of Hendrickje

Stoffels from 1654 and the wooden

press of Plantin’s

house in Antwerp). The

discovery

of photosensitive reproduction processes (the technique of

gum dichromate is part of the whole process) around 1850 and

in the field of printing the invention of the Linotype

(Ottmar Mergenthaler) and the Monotype (Tolbert Lanston)

around 1880 revolutionized reproduction techniques. Their

purpose was to reproduce works more easily than the use of

engraving and especially to make a very large number of

prints.

In 1832, Gustav Suckov discovered chromates were sensitive

to light. In 1839, Mungo Ponton noticed that a paper

soaked in a solution of potassium bichromate was sensitive

to light. In 1840, Edmond Becquerel noted that sensitivity

to light could be increased if the paper was coated with

starch or gelatin. In 1852, William Henry Fox Talbot

showed that colloids, such as gelatin or gum arabic,

became insoluble after being mixed with potassium

bichromate and after exposure to light. In 1855, Alphonse

Louis Poitevin patented the charcoal process, which

consists of adding charcoal to the colloid + potassium

bichromate mixture. In 1858, John Pouncy used colored

pigments with the gum arabic + potassium bichromate

mixture, defining the bichromate gum technique and thus

obtained the first colour prints. The great photographer

who used the bichromate gum technique at the beginning of

the 20th century was Robert

Demachy.

Watercolor or gouache are mainly made up of a

binder, gum arabic, made of acacia sap, and pigments which

define colour. Gum arabic is a water-soluble glue. It is

said to be reversible, because after drying it can be

dissolved again into water. Paints using gum arabic as a

binder are reversible, and when painted and dry, they can

be washed because gum arabic dissolves in water. If

potassium bichromate is added to the water + gum arabic +

pigment mixture, a photosensitive paint is obtained which,

after exposure to UV, becomes insoluble. To make a

bichromate gum print, a layer of the photosensitive

mixture is painted on watercolour paper. When the

photosensitive layer is dry, it is covered with a negative

and exposed to UV radiation. After exposure, one puts the

paper in water. The parts of the photosensitive layer

which have been exposed to UV adhere to the paper, the

others will dissolve in water. We can therefore reproduce

a photo, a drawing, an etching or a flower ... using the

technique of bichromate gum. You can superimpose several

prints of different colours. It is a technique that lies

between engraving, printing, painting and photography. It

is a simple process which gives very good results.

This technique is particularly well suited to

reproduce Rembrandt's drawings and etchings. It does not

provide a simple copy, it makes it possible to obtain

stable prints which are more beautiful than photographs.

It therefore offers the possibility of exploring and

presenting the fascinating world of Rembrandt's drawings

and studying their links with his etchings. However, it is

an artisanal process which takes a long time to implement

and does not allow large numbers of prints.

Omval (1641), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}, depicts a village located on the outskirts of

Amsterdam, along the Amstel River. This etching is an

iconic work by Rembrandt, in which he captures life on the

river: a pedestrian interacts with the occupants of a

passing boat, while, almost imperceptibly, lovers hide in

the foliage behind a tree. The lovers symbolize freedom

from religious conventions, serving as a subtle defiance

by Rembrandt against the religious authorities who had

condemned his lifestyle as immoral. This etching breathes

life, far from giving the impression of a static image.

For Rembrandt, the village of Omval, though the subject of

the etching, becomes secondary to the vibrancy of the

riverbank and the flowing water. Notably, in the upper

right corner of the etching, small strokes made by

Rembrandt can be seen, used to test the point that allowed

him to work through the varnish layer. True to his free

spirit and indifferent to public opinion, Rembrandt is one

of the very few etchers to leave his trials or even his

mistakes visible on the plate.

The de Run

mill in Omval (circa 1688-90), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}, is an etching made by Jan Vincentsz van der Vinne,

after Laurens Vincentsz van der Vinne. This etching,

produced about fifty years after Rembrandt’s, also depicts

life on the river at Omval. From a technical perspective, it

is a very beautiful etching. However, it clearly illustrates

the difference in subject treatment between Rembrandt and

his contemporaries, highlighting the unique freedom and

expressiveness that Rembrandt brought to his drawings and

etchings.

Rembrandt had a very strong personality, he never let

himself be influenced by what people might say,

conventions or fashion changes, his only concern was to

represent life as it was and he let himself be guided by

extraordinary inspiration and vision. This way of doing

confused many of his contemporaries and great collectors.

For example The

Night Watch painting was admired but

found disconcerting. His painting The

Conspiracy of the Batavians under Claudius Civilis (1661), made at the request

of the Amsterdam city hall, was rejected by the latter.

Finally, some of his etchings, considered immoral or

vulgar, were never acquired by certain great collectors.

His way of life was considered immoral by religious

authorities and many of his contemporaries, and note that

even at the peak of his glory, he was never invited to

Muiden Castle, where the influential circles of

Amsterdam's artistic life met.

His sentimental life was not a

long, calm river. In 1634, he married Saskia van

Uylenburg, his great love. His first three children did

not survive, only the fourth, Titus, lived to become an

adult. Saskia died in 1642. He then started a liaison

with Geertje Dircx, but then again, his new love with

Hendrickje Stoffels caused a particularly dramatic break

with Geertje. With Hendrickje, he had a daughter,

Cornelia. Hendrickje died probably of the plague in 1663

and Titus died of the plague in 1668, a year before

Rembrandt.

His works

often contain hidden messages. For example, the painting The

Return of the Prodigal Sun (1668 -

1669). Rembrandt wanted to represent the prodigal son

received by his father and his mother whereas on the

painting only the father receives the son, he therefore

suggested the presence of the mother by painting a woman's

hand and a man's hand for the father. It is painted in

such a remarkable way that it is not shocking and is not

noticeable at first sight. In the painting Landscape

with the Stone Bridge (circa 1638), the light

which crosses a very dark and tormented sky, illuminates

the canal, the bridge and the farm, places of life,

while the church receives no light.

Rembrandt, in addition being a

painter, was also an art dealer and a great

collector of works, various objects and clothes

which he used for his paintings. He was in constant

conflict with art dealers because he wanted the

works to be paid their fair price. They took revenge

when they could, and came to an agreement during the

sale following his bankruptcy so that the prices

remained ridiculously low, leading to a colossal

failure. At the height of his glory, Rembrandt made

a lot of money, but spent it easily, several factors

including a hazardous investment made that he could

no longer repay the mortgage for his house. After

his bankruptcy and the sale of all his property

(1656 - 1658), Rembrandt continued to paint and

produced some of his most beautiful paintings. He

received some orders, but died in misery. After his death there was not

enough money left to pay him a grave.

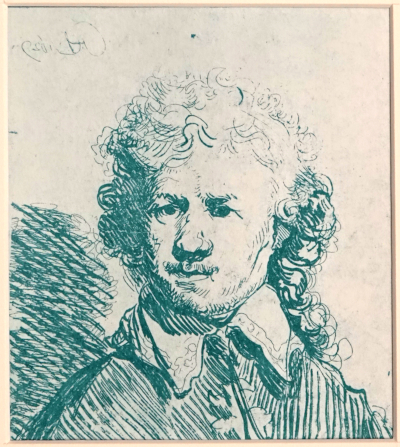

Self-portrait (circa 1628-29, Benesch, B 54, circa

1629, Schatborn &

Hinterding, D

628), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam},

is a drawing made with brush and pen during the Leiden

period. It is one of the earliest preserved

self-portraits by Rembrandt. The artist created

numerous self-portraits, not only in drawing but also

in etching and painting. These works allowed him, from

the very beginning, to perfect his etching technique

and study facial expressions to convey different

emotions, such as fear, astonishment... Later,

his self-portraits also became a way to track the

evolution of his face throughout his life. His last

painting is a self-portrait. The main characteristic of

his self-portraits lies in the emotion and humanism they

convey. In his works, he frequently portrayed himself.

When he became famous, many people wanted to acquire a

portrait of Rembrandt, which motivated him to produce even

more self-portraits.

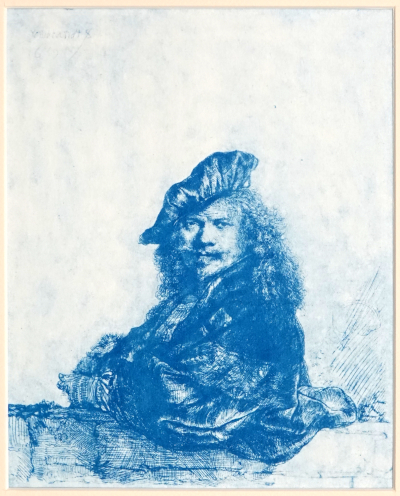

Self-portrait

(circa 1629), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}, etching

made from the drawing Self-portrait

from 1628-29, is an etching made after the drawing Self-Portrait of

1628–1629. It is one of Rembrandt's earliest

etchings, as he began etching around 1625–1626. To

preserve the flexibility and spontaneity of the

line, Rembrandt drew directly onto the metal plate,

as he would on a sheet of paper, resulting in a

reversed print. The

engraving technique that maintains this flexibility

and spontaneity is etching. In this technique, the

copper plate is first coated with a varnish. Rembrandt

then draws on it with a fine point, removing the

varnish. The plate is then immersed in an acid bath

(known as aqua fortis in the 17th century), which bites into the

copper where the varnish has been removed. It is

interesting to compare this etching with Self-Portrait with Arm Resting on a Stone

Ledge, made ten years

later. When drawing or painting a self-portrait,

Rembrandt looked at himself in a mirror, causing the

image to be reversed. However, when etching a

self-portrait based on one of his drawings, he would

reproduce the drawing onto the metal plate, and the

final print would be reversed compared to the original

drawing. As a result, the final print becomes a

non-reversed representation of Rembrandt, as he would

have appeared in reality. Rembrandt’s most beautiful

self-portrait is probably the 1639 etching, which

could be considered a true “photograph” of the

artist at that moment in his life.

Self-Portrait with Arm

Resting on a Stone Ledge (1639),

{Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam},

is an etching to be compared with the Self-Portrait

of 1629. At this time, Rembrandt reached the peak

of his etching artistry, creating one of his most

beautiful self-portraits. However, on the right

side of the etching, he left a rough sketch and

additional pencil strokes (the stones of the

wall). These elements suggest that this print is

probably one of the first, and that Rembrandt

questioned whether he would continue working on

the plate. Ultimately, he deemed the etching

complete and left it as it was. What seems to interest him most is the

portrayal of his facial expression and the luxury of

his clothing. The sketched lines also indicate a

certain nonchalance towards artistic conventions and a

sense of detachment from the image he projects.

Rembrandt appears to mock the idea of formal

perfection, favoring a more spontaneous and personal

representation. The sale of prints from his etchings

provided a regular and significant source of income

for the artist. This etching would later be followed

by the painting Self-portrait

at the age of 34.

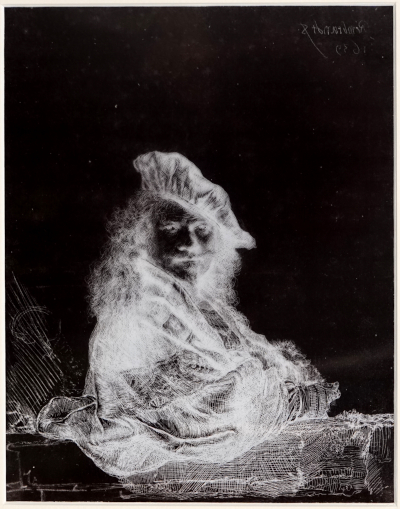

Above,

one can see the transparent used in the gum

bichromate technique to reproduce the etchving Self-Portrait

with

Arm Resting on a Stone Ledge

(1639). The transparent is placed on the sheet

painted with the photosensitive watercolor, and

the whole setup is then exposed to UV radiation.

This radiation passes through the transparent in

the white areas, which are clear. After

exposure, the sheet is immersed in water. The

parts of the photosensitive layer that were

exposed to UV adhere to the paper, while the

others dissolve in the water. In this way, the

reproduction of Rembrandt's etching is obtained.

The exposure time to UV radiation

depends on the color of the watercolor used. In the

gum bichromate technique, the transparent plays a

similar role to that of the metal plate in etching,

serving as a support for reproduction.

We will focus on Rembrandt's drawings as well as his

etchings, which are inseparable from his drawings.

These two mediums were Rembrandt's preferred means of

carrying out his experiments on how to depict life as

he observed it around him. Rembrandt was one of the

greatest draftsmen and etchers of all time. Alongside

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Käthe Kollwitz

(1867–1945), he was one of the artists who best

expressed the feelings of the human beings and animals

he drew, as well as the atmosphere of the scenes or

landscapes he wished to represent.

The main characteristic of Rembrandt's drawings is

the freedom of line and the sometimes completely

unpredictable nature of the stroke. In his

documentary “Le mystère Picasso”

(1956), Henri-Georges Clouzot attempted to answer

the question: what goes on in a painter's mind when

he works? We can trace Rembrandt's creative process

by observing how his preparatory drawings, sometimes

very rudimentary, allowed him, when he felt

ready—sometimes after several years of reflection—to

produce a masterpiece. The final result, technically

unsurpassable, has the appearance of the greatest

magic tricks: seemingly effortless, yet technically

incomprehensible, and nevertheless perfect (see, for

example, the etching The

Hundred Guilder Print

and its preliminary studies). We can follow the various problems Rembrandt

solved at each stage of his work. In the first phase, he

analyzed issues of movement and construction. In the

second phase, once these problems were understood, he

focused on the expression of characters or animals, as

well as on capturing the atmosphere of the scene he was

depicting. Finally, in a third stage, he placed shadows

and lights to indicate volumes and the hierarchy of

planes. Rembrandt also enjoyed copying the old masters

to enrich his practice.

He probably made sketches

every day. Over forty years, based on three sketches

per day, it can be estimated that he produced a

minimum of forty thousand sketches or drawings. Only

certain drawings—such as landscapes, biblical

scenes, or scenes of everyday life—can be considered

highly finished works. But most of the time, they

were intermediate sketches, which unfortunately did

not attract the interest of his contemporaries or

collectors. As a result, the vast majority of his

preliminary drawings have disappeared.

Rembrandt had many students who drew in his style.

Since most of the drawings were neither dated nor

signed, it can be extremely difficult to date and

attribute the drawings to Rembrandt with certainty.

After his bankruptcy and

the sale of his house, press, collections, and

possessions in 1658, Rembrandt had to move in 1660 and

focused more on painting. Far fewer drawings from the

period 1660–1669 have survived.

Rembrandt's

method of study

When

Rembrandt observes a scene for a few seconds or imagines

it, he breaks down the difficulties into several stages to

better understand them.

In the

first stage, Rembrandt

analyzes and seeks to understand the construction,

proportions, and/or movement of the scene. However, he

draws the scene in a completely different way

depending on whether he observes a static or

quasi-static scene (i.e., one with slow movement) or a

scene with rapid movement (for example, dancers or a

man mounting a horse). In

the case of a static or slow-moving scene, Rembrandt’s

drawing almost resembles a photograph and corresponds to a

freeze-frame of the film he observes. In contrast, when he

observes a scene with rapid movement, Rembrandt’s drawing

presents an overlay of photos from the film that

illustrate the quick motion. To illustrate these two

variants of the first stage, we will present two drawings:

Couple

of Beggars with a Dog

(page 17) and Country

Couples Dancing (page 18). When Rembrandt observes a scene where one part

is quasi-static and another is in rapid motion, he

combines both variants into the same drawing, as seen in A Man Helping a rider to Mount His Horse.

When creating drawings corresponding to this first stage,

Rembrandt sketches quickly, immediately after observing

the scene, a process that generally lasts no more than

thirty seconds.

In

the second stage , Rembrandt

seeks to understand the expression of the characters

or animals present in the scene. To illustrate this

stage, we will present two drawings: The

Sacrifice of Manoah

and Soldiers

Carousing with Women.

Some studies combine

the methods of the earlier stages with this second stage.

In one part of the drawing, Rembrandt studies the

composition of the scene, in another he analyzes the

movement, and finally, in a third part, he focuses on the

expression of the characters or animals (see Two Horses at the Relay Station).

In

the third stage, Rembrandt

places shadows and highlights to indicate the

hierarchy of planes and to convey the volume of the

scene. To illustrate this stage, we will present the

drawings The Naughty

Boy, The

Soldier in the Brothel,

the etching The Angel

Leaving Tobit and His Family,

and the drawing Young Woman

Lying Down .

These

studies demonstrate Rembrandt’s extraordinary

ability to memorize, understand, and translate

the characteristics of a scene observed in

just a few seconds, as well as his exceptional

talents as a draftsman. It is worth noting that when Rembrandt sought

to solve an artistic problem, certain details of the

drawing did not interest him, and he treated them in a

deliberately sloppy or casual manner. This approach led

some critics—quite surprisingly—to claim that Rembrandt

did not know how to draw (!).

One of the great

characteristics of Rembrandt’s work is that he never

drew, etched, or painted the same subject in the same

way twice. This approach allowed him to maintain the

freshness and spontaneity of his line, whether in a

drawing or an etching. Rembrandt significantly altered

the representation of a scene when moving from one stage

to another or from one technique to another—for example,

from drawing to etching, or from drawing or etching to

painting. This method not only enabled him to explore

different ways of depicting the scene but also to solve

the technical challenges it presented. Thanks to this

approach, Rembrandt could revisit the same theme over

several decades without ever repeating himself,

demonstrating his exceptional imagination and memory. It

is worth noting that such remarkable skills are

maintained and developed through practice. For instance,

Katsushika Hokusai decided to draw a different lion

every day, eventually creating several hundred of them!

When Rembrandt

draws scenes corresponding to the first step, he

draws the sketch on the spot just after observing

the scene (observation which lasts about thirty

seconds at most).

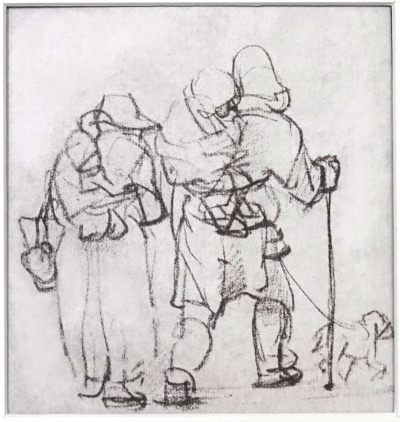

Couple of Beggars with a Dog

(circa 1647-48, Benesch, B 751, Schatborn

& Hinterding, D

390), {Albertina, Vienna}. The drawing Couple of Beggars with a Dog illustrates

how Rembrandt studies the construction of a quasi-static,

ephemeral scene—that is, one characterized by slow

movement. The lines are simple, outlining the forms of the

characters and the dog without dwelling on precise details

like hands or clothing. Yet,

the atmosphere of the scene is already perfectly conveyed:

one can sense the slow, trudging walk of the figures and the

contrast between the parents' effort and the peaceful sleep

of the children carried on their backs. This sketch is a

true freeze-frame of the “film” that Rembrandt is watching,

showcasing his extraordinary ability to memorize and analyze

a scene observed in just a few seconds. It is important to

remember that Rembrandt drew daily, both in his studio and

during his walks. He sketched life wherever he was—in the

street, the countryside, taverns, and all the places where

he could observe everyday reality.

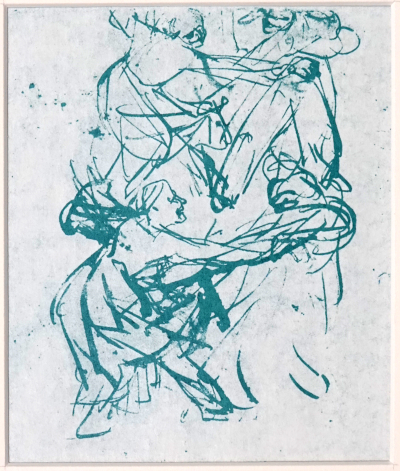

Country

People Dancing (circa 1635, Benesch, B

258 verso), {Graphische Sammlung,

Munich}. This drawing

depicts two country couples dancing at a

festivity. It demonstrates how Rembrandt

approaches the challenge of movement in a

fleeting and rapid scene. Unlike his treatment

of quasi-static scenes, here he seeks

primarily to understand and suggest movement

rather than precisely delineate the

characters’ forms. No detail is truly defined: with just a

few strokes, he evokes the swaying of the dancer

leading his partner, enhancing the sense of

movement by doubling the dancers' arms and the

woman's legs. This drawing gives the illusion of

superimposed successive images, like snapshots

from a rapidly moving film (see also the drawings

A Man Helping a Horseman

to Mount His Horse on

page 19 and Two Horses

at the Relay on page

23). The impression of dance and dynamism emerges

powerfully from this spontaneous sketch, created

with just a few lines. Rembrandt does not aim to

accurately represent the dancers but rather to

convey their momentum and liveliness. As a

finishing touch, he draws the women’s faces,

clearly expressing their amusement, while the

man’s head is merely sketched. This depiction of

the women's faces, reflecting their joy,

corresponds to the second stage of his method, in

which he focuses on conveying the characters’

emotions.

Combination of the two

variants of the first step

When Rembrandt observes a scene part of which

is quasi-static and part is rapid movement, he

combines the two variants into a single

drawing.

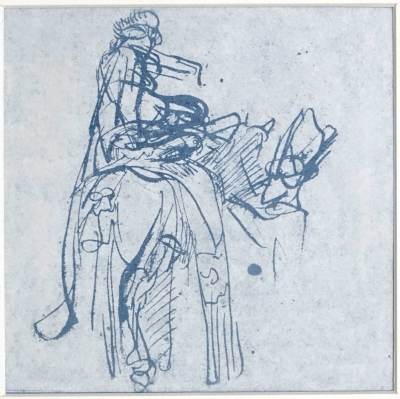

A

man helping a rider to mount his horse

(circa 1637, Benesch, B 363 recto, circa

1640-41, Schatborn &

Hinterding,

D 48), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}.

Rembrandt observes a man helping a rider to

mount his horse. This drawing is a perfect example

of how Rembrandt combines a quasi-static part and

a rapidly moving part within the same composition.

The quasi-static part of the drawing is

represented by the horse and the man standing

beside it, drawn simply and precisely, like a

freeze-frame. Rembrandt sketches the horse's

hindquarters and a leg, hints at the head and

neck, and roughly draws the man assisting the

rider. The horseman is depicted with his left foot

in the stirrup and his left hand holding the

saddle, right at the moment he is mounting the

horse. The rapidly moving part corresponds to the

horseman in the act of climbing onto his horse. To

capture this dynamic motion, Rembrandt uses an

image overlay technique, doubling the right arm

and torso, and tripling the horseman’s right leg.

This approach perfectly conveys the momentum and

difficulty of mounting the horse, creating an

impression of movement with just a few swift and

energetic strokes. On the verso of this sheet,

Rembrandt drew A Rider with a Quiver, suggesting that he quickly moved from

dynamic study to a more composed image. The sketch A

Man Helping a Rider to Mount His Horse also inspired the depiction of the rider

in the painting The Concord of the State (1637–1645, Museum Boijmans, Rotterdam),

showing how Rembrandt reused and adapted his

graphic studies in other works.

The Sacrifice of Manoach (circa 1637-40, Benesch, B 180,

circa 1635, Schatborn

& Hinterding,

D 54), {Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin}.

This drawing is one of Rembrandt's most

beautiful representations of an apparition and the

ascent of an angel. It illustrates the biblical

scene where Manoah and his wife, desperate from

being childless, sacrifice a lamb. Suddenly, an

angel appears in the flames to announce the birth

of Samson, the future liberator of Israel from the

Philistine yoke. This sketch belongs to the second

stage of Rembrandt's working method, where he

seeks to express the emotion and reaction of the

characters after having analyzed and understood

movement in a previous stage. Here, Rembrandt

captures the ascent of the angel, as well as the

backward movement of Manoah and his wife,

demonstrating their surprise, astonishment, and

fear. The focus is on the positioning of arms and

hands, as well as the angel's legs, to intensify

the sense of movement and lightness. Rembrandt

does not dwell on the precision of details such as

the characters' hands or the angel's feet, which

has unjustly earned him criticism for his supposed

inability to draw these body parts. However, this

deliberate omission clearly shows that his goal

here is to capture the essence and emotion of the

scene rather than detailing every element. The

freedom of the line and the unpredictable nature

of the stroke perfectly convey the ephemeral and

spiritual character of this apparition. Rembrandt

pays particular attention to the expression on

Manoah's face, while the expression of his wife is

less marked, indicating where his interest lies in

this study. This drawing embodies Rembrandt's way

of balancing spontaneity and technical mastery to

render the immediacy and emotional impact of a

scene. This sketch served as a source of

inspiration for other works by Rembrandt, notably

the painting The

Angel Leaving Tobit and his

Family (1637) and the etching The

Angel Leaving Tobit and

his Family

(1641). The treatment of the angel in these works

shows how Rembrandt progressively deepened and

enriched his understanding of movement and

expression, moving from preliminary study to

completed work.

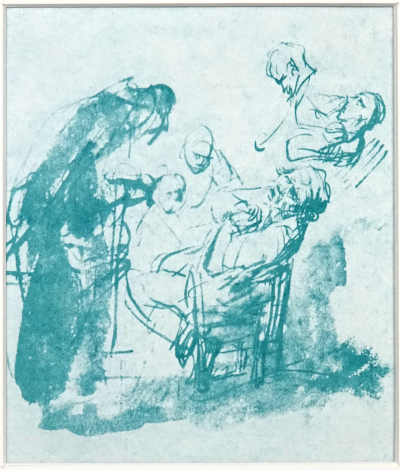

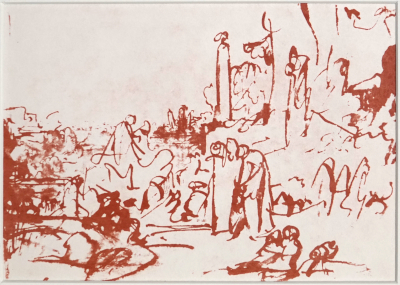

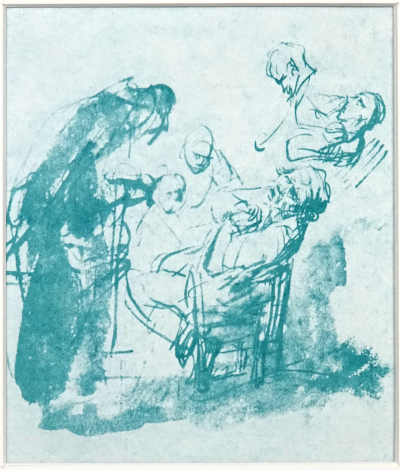

Three Soldiers Carousing with

Women (circa

1635, Benesch, B 100 verso, Schatborn

& Hinterding,

D 31), {Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin}. This drawing was

created during the same period as Rustic people dancing. It corresponds

to the second stage of Rembrandt's working

method. The artist has solved the problem of

constructing couples and is now primarily

interested in the expression of the

characters. The

soldier of the first couple tries to slip his hand

between the woman's thighs, to which she reacts

violently: she attempts to pull his hand away and

is about to slap him. Rembrandt doubles the

woman's right arm to suggest movement while

emphasizing the expression on her face. In the

case of the second couple, the artist depicts

characters having fun and exchanging caresses.

Combination of steps

1 & 2

Two Horses in the Coaching Inn (circa

1637, Benesch, B 461, circa 1629, Schatborn & Hinterding,

S 460), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}.

Two horses pulling a cart arrive to rest. The

driver places a blanket over the horses while a woman

offers one of them a piece of fruit. This study is

particularly remarkable because it combines the two

characteristic methods of the first and second stages of

Rembrandt’s study technique to depict a fleeting scene.

First, Rembrandt executes the quasi-static part, or

"freeze-frame," which allows him to structure his drawing.

This initial stage includes the cart, the driver, the

blanket, and the woman—represented in a very simple manner

without any detail. In the background, he then draws the

horse’s head as it eats the fruit offered by the woman,

corresponding to the study of movement from the first

stage. To suggest movement, Rembrandt doubles and even

triples the outline of the horse’s head, showing the

animal grabbing the fruit and beginning to chew it. This

technique of redoubling to indicate movement, known as repentir, is also observed in the

drawings Country

People Dancing and A

Man Helps a Rider to Mount his Horse. The technique of doubling to convey motion was

already employed in the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods

(for example, in ancient Egyptian art). Finally, Rembrandt

carefully details the expression of the horse’s head in

the foreground, as well as its neck and four legs,

corresponding to the second stage of his study method.

Once again, it is worth emphasizing Rembrandt’s

extraordinary memorization and analytical abilities,

enabling him to capture a fleeting scene with such

precision in just a few seconds.

Third

stage (volume)

The Naughty Boy

(circa 1635, Benesch, B 401, Schatborn

& Hinterding,

D 238), {Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin}.

This drawing corresponds to the third stage of

Rembrandt's artistic evolution. The artist has resolved

the challenges of construction, movement, and character

expression. He uses shadows and light to create a sense

of volume. To emphasize the violent and fleeting nature

of the scene, Rembrandt depicts the child's shoe coming

loose from his foot and about to fall. Although he pays

great attention to the movement of the two women and the

child, as well as to the facial expressions of the women

and the three children, he sketches the women's hands

and especially their feet only very briefly. In doing

so, Rembrandt focuses his efforts on the part of the

drawing intended to capture the viewer’s attention and

convey the dramatic character of the scene.

The Soldier at the Brothel or The

Soldier at the Tavern

(circa 1642-43, Benesch, B 529), {private

collection}. This

drawing is commonly known as The

Prodigal Son in the Company of Loose Women or The Prodigal

Son in the Tavern.

However, the man is wearing a dagger at his belt, and

his sword is placed along the armchair to the right of

the drawing, making the identification as the Prodigal

Son unlikely. This drawing represents the third stage

of Rembrandt’s method and appears as a miniature

painting. The freedom of the lines and the simplicity

of the setting are noticeable, as the artist’s main

interest lies in recreating the atmosphere and the

expression of the characters enjoying themselves.

The

Angel Leaving Tobit and his Family (1641), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}.

The archangel Raphael leaves Tobit and his

family after healing Tobit’s father’s blindness.

The family thanks the angel, who takes flight and

disappears. In this highly accomplished etching,

Rembrandt revisits the study of the angel from the

drawing The Sacrifice of Manoach. This etching corresponds to the third

stage of his artistic evolution and represents a

variation of the 1637 painting titled The Angel Leaving Tobit and His

Family. One of

Rembrandt’s unique traits is his ability to remain

interested in the same subject for several years

while offering very different representations. In

this etching, he focuses on Tobit’s family and the

characters’ expressions. It is worth noting that,

for Rembrandt, the small dog symbolizes the

family's loyalty to the archangel Raphael, whereas

in the Bible, the dog is considered a harmful and

ill-reputed animal. This demonstrates that when

depicting a biblical scene, Rembrandt imbues it

with his own personality, always prioritizing his

perspective over generally accepted conventions.

Rembrandt depicts only the lower part of the angel

in full flight, thus suggesting his rapid

disappearance from the sight of both Tobit’s

family and the viewer, witnesses to a fleeting

scene. Even the donkey appears stunned by the

angel’s ascent, enhancing the effect of surprise

and astonishment.

Young Woman Lying down, probably

Hendrickje Stoffels (circa 1655-56,

Benesch, B 1103, circa 1654, Schatborn

& Hinterding,

D 441), {British Museum, London}.

This drawing, made with brush and ink,

is one of Rembrandt's masterpieces. It reveals

what Rembrandt was capable of achieving once

he had resolved the preliminary difficulties.

One can almost trace the order of the

brushstrokes according to the amount of ink

left in the brush.

Keep the

Construction as Open as Possible

Rembrandt's passion for

freedom strongly influenced his way of

drawing. One of the characteristics of his

line is, indeed, the freedom of his stroke,

which is sometimes unpredictable. To preserve

this spontaneity, Rembrandt strives to keep

the structure of his drawing as open as

possible. The term "closing" the structure of

a drawing refers to when the initial strokes

constrain the development of the rest of the

drawing. For example, one might sketch a head

with an oval for a quick construction in the

preliminary phase, but one should not begin

with an oval if aiming to create a detailed

portrait. Similarly, when drawing a scene with

multiple figures, it is better to first

position the figures before adding the

background. To maintain the freedom of the

stroke, it is essential to delay the

introduction of constraints as much as

possible during the development of the

drawing. To

illustrate this principle, we will present a

preparatory study for the painting Saint John the Baptist Preaching. We will show how Rembrandt proceeds

when focusing his attention on a particular

character within a group.

Preliminary Study (circa 1637 by Benesch,

B139A), {Private collection} for the

painting Saint John the Baptist

Preaching.

At this stage of the work, Rembrandt

draws the heads as ovals, as he is not yet

aiming to depict details or create portraits.

He first places the figures or groups of

figures, then positions the elements of the

background. This drawing represents the first

stage of Rembrandt’s study. At the bottom

right of the sheet, he suggests the presence

of a seated woman with a child on her lap, for

whom he will later create several studies. We

will present two

of these studies.

When Rembrandt focuses his attention on a

particular character within a group, it is

very interesting to observe how he draws

the group while avoiding closing the

structure of his drawing. We will present

the two drawings Guided

by an Angel, Lot and His Family Leave

Sodom and Lot and His Daughters,

in which Rembrandt concentrates on the

main characters, particularly on Lot. In

both works, he skillfully emphasizes the

main figures while allowing the

surrounding elements to remain more

loosely defined, creating a dynamic and

open composition. This

approach emphasizes the central characters

without restricting the fluidity of the

scene, adding a sense of movement and

spontaneity to the drawings.

Guided by an Angel, Lot and his

Family Leave Sodom

(circa 1636, Benesch B 129), {Albertina,

Vienna}. Guided by an angel, Lot, his wife, and

his daughters leave Sodom, destined for

destruction by God. The angel warns them not to

look back; however, Lot’s wife, defying this

warning to glance behind, will be turned into a

pillar of salt. Lot and his daughters will later

take refuge in a cave (see the following

drawing, Lot and His Daughters). To maintain the openness of his

composition, Rembrandt begins by drawing Lot with

great detail, using shadows to define the volumes.

He then depicts the angel and Lot’s wife, who

surround and guide him, and finally sketches the

two daughters following them in a more succinct

manner. This drawing is an excellent example of a

study sheet, revealing the three characteristic

stages of Rembrandt's work. Another interesting

point is the question of the drawing’s

attribution. On the verso of the sheet, there is a

drawing likely made about ten years earlier by a

student of Lastman. This led some experts to

speculate that the drawing might not be by

Rembrandt himself, but rather a copy made by

Govert Flinck (?) or Jan Victors (?) in the years

1640–45. Legend has it that when Rembrandt picked

up this sheet to draw, one of his students said, "No, Master, don’t use that sheet for

drawing, or in three hundred years, experts

might discredit your work!"

Rembrandt merely shrugged and drew on it anyway.

Lot

and his Daughters

(circa 1636, Benesch, B 128, circa

1638, Schatborn

& Hinterding,

D 57), {Klassik Stiftung, Weimar}.

After leaving Sodom, destroyed by

God, Lot and his daughters take refuge in

a cave where wine, placed there by divine

will, is found. The two daughters find

themselves alone with their father, as

their fiancés refused to follow them.

Fearing that they will have no descendants

in this isolated place, the eldest

daughter decides to intoxicate her father

to conceive a child and convinces her

younger sister to do the same. From this

incestuous relationship, two sons are

born: Moab, founder of the kingdom of the

Moabites, and Ben-Ammi, founder of the

kingdom of the Ammonites. The drawing

shows the eldest daughter (?) encouraging

her father to drink by handing him the

cup, while Lot, already intoxicated,

begins to sway. To maintain the openness

of his composition, Rembrandt starts by

drawing Lot in a very accomplished way,

except for his legs, which are sketched

more succinctly. Then, he draws the

expressive face and hand of the eldest

daughter urging her father to keep

drinking. Finally, he sketches the

silhouette of the younger daughter and

adds a few decorative elements. This

drawing is a magnificent example of a

study sheet, showcasing the three

characteristic stages of Rembrandt's work.

It was preceded by a more accomplished

drawing, Lot

and his Daughters (circa 1631), generally

attributed to the school of Rembrandt but

possibly by his own hand, and made popular

by Jan van Vliet’s etching

in 1631.

A

Line Sometimes Completely

Unpredictable

Finally, it should

be noted that Rembrandt’s drawing is

also distinguished by a line with a

completely unpredictable stroke,

displaying remarkable virtuosity (see

for example The

Sacrifice of Manoach).

Through this technique, Rembrandt

suggests what he wishes to represent

without precisely outlining the

contours. Rembrandt typically uses this

technique at the end of a drawing’s

execution to preserve the freshness and

vitality that emanate from it, avoiding

any stiffness or rigidity. A striking

example of this approach can be found in

the Portrait

of Saskia

from 1633.

Portrait

of Saskia

(detail of the drawing dated

1633 and annotated by Rembrandt,

Benesch B 427, Schatborn

& Hinterding,

D 629), {Kupferstichkabinett,

Berlin}.

Rembrandt created the portrait

of Saskia on June 8, 1633, three days

after their engagement. This drawing,

executed with a silverpoint on

parchment, begins with the depiction

of Saskia's face, hat, and left hand,

followed by her right hand. It is

interesting to note that the right

hand lacks the finesse of the other

and resembles more of a man’s hand. It

could, in fact, be Rembrandt’s own

hand, offering a flower to his beloved

fiancée. Next, he completes the two

sleeves and the shoulder of Saskia's

garment with lines that are entirely

unpredictable. This virtuoso stroke

suggests the shoulder and sleeves

without explicitly outlining their

contours, resulting in a far more

elegant effect than if the sleeves had

been drawn conventionally. This way of

drawing without closing the

construction is characteristic of the

happy period of Rembrandt’s life,

where spontaneity and freedom of line

reflect his state of mind.

To capture

the observer’s attention

For

Rembrandt, the important thing is

not merely to draw the whole

scene, but to focus on the part of

the drawing that interests him and

allows him to express what he

wants. This is the part that

should capture the observer’s

attention (see, for example: Three Soldiers Carousing

with Women,

Horses

at the Relay Station,

The

Naughty Boy, Accompanied

by an Angel, Lot Leaving Sodom

with His Family,

Portrait

of Saskia).

This way of approaching the

subject can also be found in

certain paintings executed after

1650. It

is worth noting that, in the

treatment of a subject in a

drawing or print, the theme

becomes secondary to the life he

breathes into his works (for

example: Omval).

To complete our discussion, we

will also present the painting A Woman Bathing in a

Stream and

Rembrandt’s studies of a

seated woman, as well as the

lithograph The

Mother and her Child

by Käthe Kollwitz and the print The Great Wave off

Kanagawa by Katsushika

Hokusai.

A

Woman Bathing in a Stream

(1654), {National Gallery,

London}. Rembrandt focuses on

the face of the woman entering

the water, thus expressing the

pleasure she feels at the

thought of bathing. He also pays

particular attention to the

small ripples created by the

woman’s legs in the stream,

suggesting the movement of her

entry into the water. The face

and the ripples on the water are

the only parts of the painting

treated with great delicacy and

meticulous finishing. In

contrast, the dress is painted

with remarkable virtuosity,

using broad brushstrokes and a

heavy application of paint. The

woman’s right hand, lifting the

dress, is sketched in a succinct

manner, yet this simplification

does not seem jarring unless one

focuses on the details. This way

of painting was completely

misunderstood by Rembrandt’s

contemporaries, who criticized

him for producing unfinished

works.

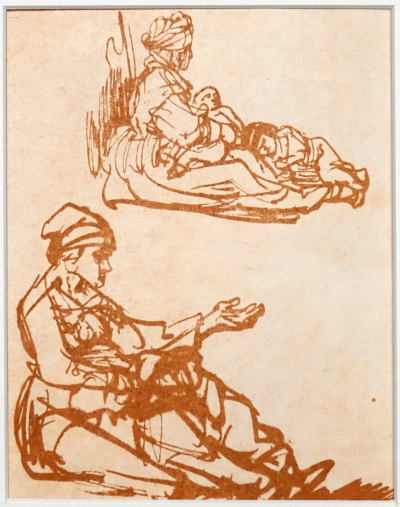

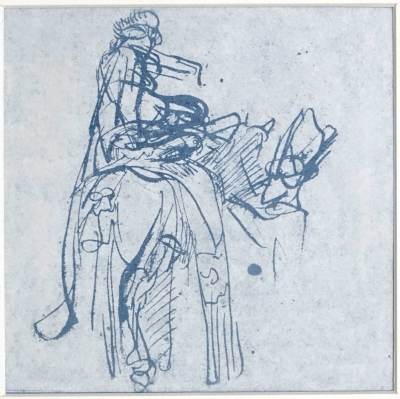

Studies

of a Seated Woman

(circa 1633, Benesch,

B179, circa 1639,

Schatborn

& Hinterding,

D 343), {Musée du Louvre,

Paris},

used in the painting

Saint John the

Baptist Preaching.

When Rembrandt

sketches the seated woman at

the bottom of the sheet, he

does not outline her face with

an oval, as he is focusing on

studying her expression. In

contrast, for the seated woman

at the top, he does use an

oval for the face, as he is

not interested in detailing

her features or exploring her

expression. Since Rembrandt

aims for a continuous, fluid

line—rather than composing his

drawings from separate,

disconnected strokes—he often

struggles with rendering hands

accurately. In the study of

the woman at the bottom, he

concentrates on her facial

expression and left hand.

While the hand is not drawn

with great precision, it

effectively conveys that the

woman is a poor beggar,

reaching out for money or

food. In the upper study,

Rembrandt focuses more

precisely on the

representation of two

children, drawing them with

greater clarity than in the

lower study. These two seated

woman studies were later

followed by a third, distinct

study. Notably, all three

differ from the final painted

version.

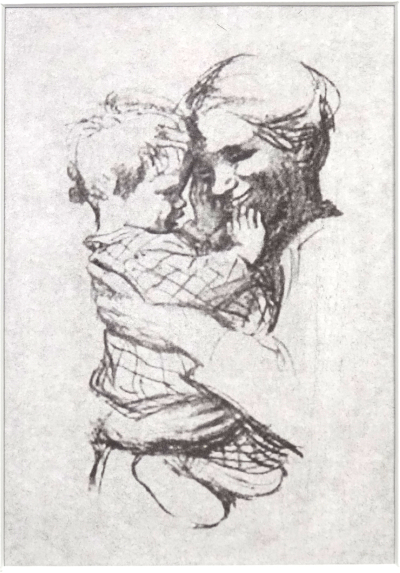

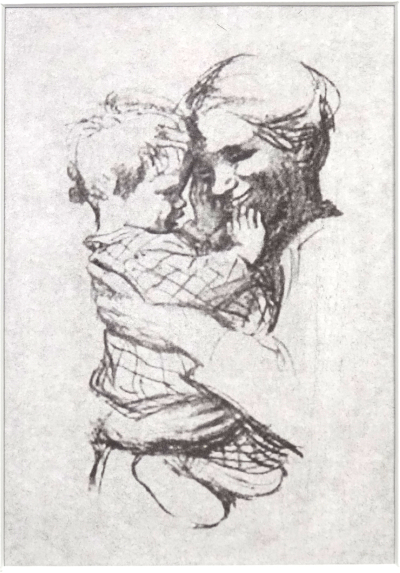

The

Mother and her Child (1916,

Lithography) by Käthe

Kollwitz

is a poignant and

emotive work, characteristic

of the artist's

expressionist style. Known

for her social and

humanistic works, Kollwitz

often explores themes such

as suffering, love, and

class struggle. In this

lithograph, she meticulously

depicts the faces of the

mother and child, as well as

the child’s two hands. She

highlights the intensity of

maternal love through the

profound and sensitive

expressions on their faces.

The gazes of both

figures—the mother and the

child—are the focal point of

the piece. It is through

these gazes that the artist

conveys the emotions and the

intimate bond that unites

them. The mother gazes at

her child with immeasurable

love and palpable

tenderness, while the child

appears both dependent and

confident, feeling secure in

the maternal embrace. The

lack of precise detail in

the depiction of the

mother’s hands reinforces

the idea that technique is

not the core of the work,

but rather the pure

expression of feelings. This

deliberate inaccuracy can be

seen as a simplification

intended to allow the viewer

to focus on raw emotion

without distraction. The

representation of the mother

and child, devoid of

ornamentation or

embellishment, gives the

work a sincerity and

universality that transcends

technique, directly touching

the viewer’s soul.

The Great Wave off

Kanagawa, a woodblock

print by Katsushika

Hokusai (1831), is part

of the famous series Thirty-Six

Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku

Sanjūrokkei). Similar to

how Rembrandt's etching

Omval renders the

subject secondary, Mount

Fuji becomes less

prominent here; what

truly interests Hokusai

is, above all, the

fishermen's way of life.

He depicts a massive

crashing wave off the

coast of Kanagawa Bay,

with Mount Fuji

appearing in the

background. It is

noteworthy that,

although Mount Fuji is a

sacred symbol of Japan,

Hokusai focuses on the

fishermen, whose fragile

boats struggle against

the vastness of the sea

and the power of the

wave. This approach

reflects a form of

humanism, where the

harsh living conditions

of the

fishermen—belonging to

modest social

classes—are elevated to

the same level as Mount

Fuji, sacred yet

distant. By portraying

the fishermen's battle

against the forces of

nature, Hokusai elevates

these common figures to

an almost mythological

status, granting them

remarkable dignity

through the power of his

depiction. Through its

dynamic movement and

depth, Hokusai’s

composition is a

masterpiece of Japanese

art from the Edo period.

The great wave, with its

vibrant energy and

abstract form, has

become one of the most

recognizable images of

Japanese art and

woodblock printing.

To illustrate

everything we have

just discussed, we

present Study for

the Lamentation of

Jacob.

Study for the

Lamentation of

Jacob (circa

1635, Benesch, B

95, Schatborn

&

Hinterding,

D 40),

{Kupferstichkabinett,

Berlin}.

This drawing

perfectly embodies

Rembrandt’s artistic

approach and

illustrates the

principles

previously

discussed. Jacob,

the grandson of

Abraham, is depicted

in a posture of

intense lamentation,

pleading with a

specter that appears

in his distress.

Convinced that it is

a vision of God,

Jacob is, in

reality, confronted

by the specter of

his twin brother,

Esau. A vision of

God would have

caused his death.

Jacob is known as

the father of

Joseph, who was

falsely accused by

Potiphar's wife of

attempting to seduce

her. In this

study, we find

Rembrandt’s

exceptional mastery of

line: a freedom of

execution that

preserves the

freshness of the

drawing while

maintaining remarkable

emotional power. The

contours remain open,

allowing shapes to be

suggested rather than

fixed, reinforcing the

impression of movement

and spontaneity. The

line work is both

dynamic and subtle,

enabling emotions to

emerge almost

instinctively. This

virtuosity contributes

to the humanity that

emanates from the

work, bearing witness

to Rembrandt’s

profound artistic

depth.

Evolution

of Rembrandt's

line

As previously

mentioned, the use of

a line with a

completely

unpredictable stroke

is characteristic of

the happy period of

Rembrandt’s life. His

style evolved

considerably toward

the end of his life,

particularly after

1655. After his move

in 1660, when his

press had been seized,

Rembrandt produced

very few etchings. It

is also possible that

his output of drawings

decreased, especially

since very few

drawings from this

period have survived.

This stylistic

evolution became more

pronounced after the

death of Hendrickje

Stoffels in 1663. To

illustrate this

evolution in

Rembrandt’s line, we

will present the

drawing Diana

and Actaeon.

Diane

and Acteon, (circa

1662-65, Benesch -

B 1210, circa

1656, Schatborn

&

Hinterding,

D 161),

{Kupferstichkabinett,

Dresden},

is probably one

of the last known

drawings by Rembrandt.

In his later years, he

revisited this theme,

creating a free

adaptation of an

engraving by Antonio

Tempesta (1555-1630).

Although the drawing

retains a great deal of

freedom in execution, it

has been greatly

simplified: curves are

often replaced by

straight lines, and the

stroke becomes stiffer,

more angular, and

rudimentary. Rembrandt

more frequently used

reed or bamboo, which

allowed him to achieve a

line that was both

vigorous and highly

nuanced. One can notice

the extraordinary

efficiency with which he

represents the heads and

faces of Diana and her

attendants. After the

death of Hendrickje

Stoffels and all the

hardships he had

endured, Rembrandt, now

beyond the pain, sought

to avoid any unnecessary

embellishment,

prioritizing simplicity

and the essential. The

unpredictable strokes,

so characteristic of his

earlier periods,

disappear from his late

drawings. This stylistic

evolution may have been

amplified by health or

vision problems, and it

is also evident in his

paintings. However, this

style confused his

admirers, who considered

his works unfinished and

were no longer eager to

purchase them. Yet,

Rembrandt, detached from

the opinions of

potential buyers,

continued his personal

artistic quest.

Rembrandt's

perception and

representation

of volume

As we mentioned

earlier, Rembrandt

never drew the

scenes he studied in

the same way twice.

The final version of

the scene he wished

to represent was

always different

from the preparatory

studies he had made.

This working method

allowed him to

approach the subject

or scene in three

dimensions, thereby

strengthening his

spatial

understanding of the

motif. Arnold

Houbraken

(1660–1719) reports

in this regard: “It often

happened that he would

sketch a face in ten

different ways before

reproducing it on the

canvas.” As a draftsman,

etcher, and painter,

Rembrandt always sought

to convey the volume of

the scene depicted, in a

way that gave the viewer

the impression of

observing not a static

image projected in two

dimensions, but a

living, natural scene,

and therefore more

human. Early on, he

understood that one of

the ways to resolve this

issue was through the

use of chiaroscuro and,

more broadly, the play

of shadows and light.

This is already clearly

visible in the painting

The

Parable of the Rich

Fool

(Gemäldegalerie,

Berlin), created in

1627, three years after

he set up his studio in

Leiden. To accentuate

the sense of volume in

his paintings, Rembrandt

frequently depicted

backgrounds in a blurred

manner, thus enhancing

the illusion of depth.

The portrait of

Jan Cornelis

Sylvius is the

most

extraordinary

example of

Rembrandt's

exploration in

etching, aiming

to give the

viewer an

impression of

volume, life,

and naturalness.

Portrait

of Jan Cornelis

Sylvius,

Rembrandt (1646),

{Rijksmuseum,

Amsterdam}.

To

enhance the

impression of

volume,

Rembrandt

imposes a

precise viewing

angle on the

spectator by

drawing the

perspective of

the mat's bevel.

This positioning

places the

viewer slightly

below and to the

right of Jan

Cornelis. The

light,

meanwhile, also

comes from the

right but from a

source

positioned

higher than the

model. To

reinforce

the effect of

relief, Rembrandt

makes the right

hand, the book, and

Jan Cornelis’s head

literally emerge

from the plane of

the image by casting

their shadows onto

the mat. This

technique gives the

portrait a striking

sense of life and

humanity. Rembrandt

transcends mere

anecdote to create a

work that goes

beyond a simple

projection on paper.

The

catalogues

of Rembrandt's

drawings

(An

example of a

problem of

attribution)

The two most

comprehensive

catalogs of

Rembrandt's

drawings are Otto

Benesch's catalog,

The Drawings

of Rembrandt,

(1973), in six

volumes, and the

catalog by Peter

Schatborn and Erik

Hinterding, Rembrandt:

All the Drawings

and Etchings,

(2019). There are

also many other,

more partial

catalogs, which we

will not list

here.

As previously

mentioned, most of

the drawings by

Rembrandt or his

circle of students

were generally

neither

dated nor signed,

making their

dating and

attribution

extremely

difficult to

establish with

certainty.

The Benesch

catalog (1973)

provides a

description, a

history, and the

reasons for

attributing each

drawing to

Rembrandt. The

Schatborn and

Hinterding

catalog (2019)

is a revision

and update of

the Benesch

catalog (1976),

using the

criteria

explained in

Schatborn &

van Sloten

(2014). The

latter is

intended for a

broad audience

and does not

include

descriptions,

histories, or

explanations of

the reasons for

attributing each

drawing to

Rembrandt.

The

main

issue with the

Schatborn (1985)

and Schatborn

& Hinterding

(2019) catalogs,

based on the

criteria from

Schatborn &

van Sloten

(2014), is that

they do not take

into account two

fundamental

characteristics

of Rembrandt’s

drawing

technique. The first

characteristic

concerns the way

Rembrandt approaches

a subject: when he

discovers a subject,

he begins by

studying its

proportions and

movement. If the

subject moves

slowly, he creates a

“freeze-frame” (for

example, Beggar

Couple with a

Dog). However,

if the subject moves

quickly, he opts for

an overlay of images

that depict motion

(for example, Dancing

Peasant Couple, A Man

Helping a Rider

Mount His Horse, Three

Soldiers

Carousing with

Women, Two

Horses at the

Relay or the

Farm, The

Horse

Eating a Fruit

from the Woman’s

Hand). The

second overlooked

characteristic is

that Rembrandt never

drew the same

subject in the same

way twice. In other

words, he never

copied a drawing or

an etching, allowing

him to maintain

great spontaneity

and freshness of

line in his

drawings, etchings,

and paintings.

It is very

interesting to

observe how

these two

shortcomings can

influence

conclusions and

deductions,

taking as an

example the

drawing A

Man Helping a

Rider Mount

His Horse.

This drawing

combines both

methods from the

first step: it

features a

"freeze-frame"

for the almost

static part,

with the horse

and the man

assisting the

rider, and an

overlay of

images depicting

the rider’s

movement as he

swings his leg

over the saddle

to mount the

horse (see page

19). On the

reverse side,

Rembrandt drew a

rider with a quiver,

suggesting that

immediately after

completing this

study, he turned the

sheet and drew a

rider wearing a

feathered hat on his

horse. This sketch

would later be used

by Rembrandt in the

etching The

Baptism of the

Eunuch (1641).

Rider with a

Quiver, (circa

1662-65, Benesch – B

1210), {Rijksmuseum,

Amsterdam}. This

sketch will be used

latter by Rembrandt

for the etching The

Baptism of the

Eunuch

(1641).

To

preserve the

freshness and

spontaneity of the

line, Rembrandt

etched a variant of

the sketch A

Rider with a

Quiver without

reversing the

drawing. This is a

typical working

method of Rembrandt.

Regarding the

drawing A Man

Helping a Rider

Mount His Horse,

Schatborn (1985,

page 46) does not

write, « Rembrandt

created a

beautiful study of

the movement of a

rider mounting a

horse », but

instead concludes

that « Rembrandt

tried to draw a

rider mounting a

horse, but he does

not seem to have

found a

solution... ».

It is interesting to

analyze the

consequences of this

initial

misunderstanding.

Indeed, Schatborn

deduces that « This

shows that

Rembrandt did not

draw from a model

but worked from

memory... » To

explain the drawing

of the rider on the

reverse side of the

sheet, he asserts: «

The drawing on

the reverse is not

by Rembrandt but

was added by a

dealer to make the

sketch of the

rider mounting his

horse more

attractive for

sale! »

Therefore, Schatborn

(1985) does not

attribute the

drawing A Rider

with a Quiver

to Rembrandt, and

this sketch is not

included in the

catalog of

Rembrandt's drawings

by Schatborn and

Hinterding (2019).

Legend has it that

after finishing

these sketches,

Rembrandt went to a

tavern with one of

his students. The

student, after

examining the

sketches, said to

Rembrandt: « Master,

you should explain

your sketches and

your working

method, for one

day an expert

might write »:

« Rembrandt

tried to draw a

rider mounting a

horse, but he does

not seem to have

found a

solution... »

Rembrandt’s response

has not reached us,

but it is easy to

imagine. Indeed,

Rembrandt and his

circle of students

had little regard

for art critics,

who, without

practicing drawing,

etching, or painting

themselves, believed

they were connected

to a higher truth

(see the drawing Satire

of the Art Critic).

These examples help

to understand the

difficulty of

attributing drawings

to Rembrandt or his

students, as well as

the potential

fragility of

experts'

conclusions. They

also demonstrate

that having drawing

skills is not

without value when

it comes to fully

grasping Rembrandt's

drawings and method,

especially in

distinguishing a

movement study from

a finished drawing.

Satire of the Art

Critic (c.

1644, Benesch –

A35a, c. 1638,

Schatborn &

Hinterding, D 318),

{Metropolitan Museum

of Art, New York}.

This work is a

caricature of an art

critic, drawn by

Rembrandt or one of

his pupils. An

ironic twist in the

history of

attributions:

Benesch (1973)

attributes this

drawing to a pupil

of Rembrandt, while

Schatborn &

Hinterding (2019)

attribute it

directly to

Rembrandt.

References

for this section :

- Benesch O.,

1973, The

Drawings of

Rembrandt (six

volumes),

Phaidon

- Schatborn P.,

1985, Catalogue

of the Dutch and

Flemish Drawings

in the

Rijksprentenkabinet,

Volume 4,

Rijksmuseum,

Amsterdam, page

46

- Schatborn P.

& van Sloten

L., 2014, Old

drawings, new

names,

Uitgeverij de

Weideblik, Varik

and the

Rembrandt House

Museum

- Schatborn P.

& Hinterding

E., 2019,

Rembrandt, tous

les dessins et

toutes les eaux

fortes, Taschen

|

|