Introduction

Among the scenes of intimate life that we will develop are:

- bath scenes,

- scenes of everyday life,

- scenes of harassment,

- scenes of voyeurism,

- scenes of seduction, and

- scenes of lovers.

Before presenting the etching Diana at the Bath, we will present the etching Saint Paul in Meditation, which is probably the etching that allowed Rembrandt to learn the technique of transferring a drawing onto the varnish of a plate in 1629. This technique was later applied to the etching Diana at the Bath. Two etchings from 1630 and 1631 play an important role in Rembrandt's method of etching and mastery of the etching technique: Diana at the Bath and his Self-Portrait with Hat and Ruff. In the case of the etching Diana at the Bath Rembrandt transferred a precise drawing onto the plate and the print of the etching is a faithful but inverted reflection of the drawing. The climax of this method of transferring a drawing will be reached with the etching Jan Six reading of 1647.

Transfer of a drawing onto the varnish of a plate

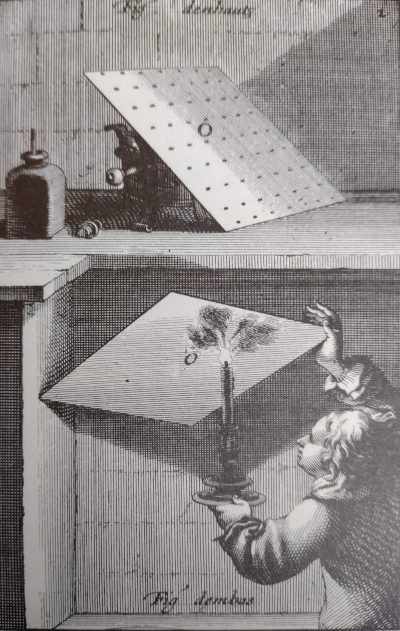

To reproduce a drawing, a print or a painting in engraving, it is first necessary to draw the reverse of the drawing, print or painting. It is also possible to obtain the reverse of a drawing in a very simple way, after having made the drawing on a sheet of paper that is not too thick, the paper is coated with oil, and becomes translucent, so you just have to turn it over to see the reversed drawing. Then the engraver has to transfer the reversed drawing onto the varnish of the plate so that the print on the paper corresponds to the original drawing. In general, Rembrandt, who wanted to preserve the freedom of line and the spontaneity of a first drawing, never made the same drawing twice when studying a subject or theme and drew directly on the plate without reversing the drawing when he engraved. His prints then appear inverted, which did not bother him at all. Nevertheless, he sometimes transferred a drawing onto a plate to make an etching, which was like copying his drawing onto the varnish of the plate. It should be noted that Rembrandt did not draw the reverse of the drawing to be engraved, nor did he coat the sheet with oil, but he did transfer the drawing onto the varnish of the plate and thus the print was reversed from the original drawing. For Rembrandt it was important to transfer the main character of the scene to be engraved. After the beginning of his collaboration with the Leiden engraver Jan van Vliet, Rembrandt learned the technique of transferring a drawing onto the varnish of a plate in 1629 by etching Saint Paul in Meditation. It was probably J. van Vliet who introduced him to this technique, which we will explain following the recommendations of A. Bosse (1645).

The first step is to :

- or whiten the varnish if we use a soft or a hard varnish. To whiten the varnish we use ceruse white which we mix with a little glue from Flanders. The mixture is melted and heated in a bowl. It is recommended to add a few drops of bile to improve the adhesion of the white on the varnish. The white is applied with a brush of pig's hair or a large cloth.

- either cover a white sheet with sanguine powder which is applied to the paper by rubbing the powder with the palm of the hand,

- or cover a white sheet with black stone powder which is applied to the paper by rubbing the powder with the palm of the hand.

- the sheet coated with sanguine powder is placed either on the blackened plate or on the whitened plate, the sanguine-coated side against the varnish,

- the sheet coated with black stone powder is placed on the whitened plate, with the black stone side against the varnish.

The last step is to make what A. Bosse calls it a reproduction or counterprint of the drawing to be engraved on the varnish of the plate:

- the sheet with the drawing to be transferred to the varnish is placed on the sheet of paper coated with red chalk or black stone,

- then the lines of the drawing are traced with a stylus (a metal point less sharp than the needles used to remove the varnish for etching). The drawing then appears in red on the black or white background or in black on the white background.

Bath scenes

The theme of Diana at the Bath

The theme of Diana at the bath with her nymphs, and its variants with Callisto and Actaeon, was dealt with repeatedly by Rembrandt over more than thirty years. He treated this theme in drawings, etchings and paintings. The first time Rembrandt dealt with the theme of Diana at the bath was in his etching of 1630, a very important etching in Rembrandt's development and mastery of etching.

Diana is a goddess from Latin and Roman mythology. She is a goddess with power over procreation, and also the goddess of the hunt and the moon. She was soon equated with the Greek goddess Artemis, goddess of hunting and childbirth. Artemis is the daughter of Zeus and Leto (one of Zeus' conquests). She is the sister of Apollo and is associated with the Moon while her brother Apollo is associated with the Sun.

Rembrandt treated three myths associated with Diana, Diana at the Bath, Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Callisto.

- In Diana at the Bath, the goddess can be depicted alone bathing, or she is shown bathing with her nymphs.

- In Greek mythology Artemis and Actaeon (Diana and Actaeon in Latin mythology). Actaeon, a great hunter, surprises Artemis (Diana) who is bathing with her nymphs. The latter, furious, transforms him into a stag and he is devoured by his own dogs. According to Euripides and Diodorus, Artemis was furious with Actaeon because, in the temple of Artemis, he had boasted of being a better hunter than the goddess.

- Callisto was a huntress and the favourite servant of Artemis (Diana) the goddess of the hunt. She had promised her to remain a virgin. Zeus, in love with Callisto, managed to seduce her by taking on the appearance of Diana and Callisto became pregnant. During a bath with Diana and her followers, Artemis discovered Callisto's pregnancy and angrily chased her away from her suite. Callisto gave birth to a son, Archas, and after his delivery, Zeus' wife Hera turned Callisto into a bear in revenge. Fifteen years later Archas, now a hunter, found himself in the forest with his mother. Zeus did not allow Archas to kill his mother and had them taken up into the sky where they formed the constellations of the Big and Little Bear.

Diana at the Bath

Diana at the Bath

Diana at the Bath (circa 1629-33), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}. To etch this plate, Rembrandt faithfully reproduced the drawing of Diana at the bath. In comparison with the drawing, he enlarges the background with a tree and foliage and adds ornaments that show that Diana is the goddess of the hunt. Diana was usually depicted with a crescent moon on her head (see the etching Diana at the Bath with her Nymphs and the drawing Diana and Actaeon Benesh A 60). The final print in the case of a transfer is the same as the original drawing, except that it is reversed. It is important to note that in Rembrandt's work, he only uses the same drawing to carry out two different steps in the case of a transfer to engrave a plate. This is quite rare in Rembrandt's engraved work. The etching resulting from a transfer no longer has the free and improvised manner that Rembrandt likes above all. He compensated for this apparent loss of freedom with an exceptional technical achievement, which is particularly evident in the etching Jan Six Reading.

Diana at the Bath with her Nymphs (circa 1694), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}. A very fine etching, from almost the same period as Rembrandt's, by Pieter van den Berge. It shows the difference in Rembrandt's treatment from that of his contemporaries, in particular how he represents Diana.

Diana and Actaeon

Woman at the Bath

Woman at the Bath (circa 1635 by Benesch, B 193A), {Nationalmuseum, Stockholm}. Very accomplished drawing which is a preparatory drawing for the painting Diana at the Bath with her Nymphs Surprised by Actaeon.

Diana and Actaeon (circa 1635-40 by Benesch - A 50), {Louvre Museum, Paris}. This drawing is attributed to a pupil of Rembrandt (Ferdinand Bol?).

Diana and Actaeon, (circa 1662-65 Benesch - B 1210, circa 1656, Schatborn & Hinterding, D 161), {Kupferstichkabinett, Dresden}. Rembrandt again tackled this theme in his late period. Although the drawing remains very free, it is considerably simplified and curves are often replaced by straight lines, the line becomes stiffer, more angular, more rudimentary. Rembrandt more readily uses reed or bamboo, which allows him to obtain a vigorous but at the same time very nuanced line. The extraordinary efficiency in representing the heads and faces of Diana and her followers is noteworthy. Rembrandt wanted to avoid superfluous brilliance, to simplify and go to the essential. The unpredictable lines no longer appear in his late drawings. This evolution was perhaps amplified by health and vision problems. It can also be seen in his paintings. It confused his admirers, who felt that his paintings were unfinished and no longer wished to buy them, but Rembrandt no longer cared what his potential customers thought.

Diana and Callisto

Diana and Callisto (dated 1642-43 by Benecsh, B 521), {Private collection}. In Roman mythology, Callisto, Diana's favourite follower, promised to remain a virgin. Jupiter, in love with Callisto, takes on the appearance of Diana, seduces her and she becomes pregnant. During a bath for Diana and her followers, Diana discovers Callisto's pregnancy. This is the scene Rembrandt drew. Rembrandt's drawing is a free adaptation of an engraving by Antonio Tempesta (1555 - 1630).

The Bathers (etching, circa 1651), {Rijksmuseum,

Amsterdam}. Rembrandt shows bathers on the banks of a

river. The impression of spontaneity that emerges from

this etching suggests that the plate was etched on the

spot. This is quite possible if Rembrandt had gone for a

walk with an already varnished copper plate with a hard

transparent varnish. Instead of drawing the bathers on a

sheet of paper, he drew them directly on his varnished

plate with a needle and dipped the plate in acid on his

return. He could then take it back to his studio to

complete it and make a new state. It is to be compared

with the etching The woman at the Brook.

Woman at the Brook (1658), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}. This etching is one of the intimate scenes Rembrandt made before his press was seized.

A woman at the Brook 1654, {British Museum,

London}. In this painting Rembrandt

focuses on the face of the woman entering the water, he

shows the pleasure of the woman going for a bath. The face

is the only part of the painting that is treated with

great delicacy and finish. The dress, on the other hand,

is painted with great virtuosity, with large brushstrokes

and a lot of impasto. The right hand of the woman lifting

the dress is painted very succinctly, but if one does not

look at it in detail, it does not shock. To convey the

movement of the woman entering the water, Rembrandt paints

and highlights the ripples caused by the woman's legs in

the water of the stream. This way of painting was totally

misunderstood by Rembrandt's contemporaries, who

criticised him for making unfinished paintings.

The Pissing Woman

The Pissing Woman (1631), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}. In this print the woman is doing her business. This etchings can be compared with the etching The Good Samaritan circa 1634. The scene takes place on a farm in the countryside and Rembrandt added a dog doing its business in the foreground. A priori this dog has nothing to do with the subject matter, but for Rembrandt the scene takes place on a farm and it is natural that a dog is there. Above all, it was Rembrandt's way of showing his total independence from the prevailing norms and of challenging the morals of the time.

Woman at the stove

Woman at the stove (1658), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}. This etching is one of the intimate scenes done before his press was seized. The model used in this etching is the same as the model in the etching Woman washing. This etching shows a woman at a stove who is probably about to wash herself.

Woman at the stove

Bathsheba's Toilet

Bathsheba's Toilet (c. 1643), {Metropolitan Museum of Art}. Bathsheba, the wife of Uriah the Hittite, is seen by King David while she is washing. This is the scene Rembrandt depicts. The king has Bathsheba kidnapped, coerced her and she became pregnant and later he send her husband into battle to be killed. After her husband's death, she becomes the wife of King David.