I - Introduction

To simplify matters, we can distinguish three periods:

- the Leiden period (1620 - 1631). Only five

preparatory drawings remain. He portrayed himself five

times in genre scenes and produced twenty-two

self-portraits in etching and eight self-portraits in

painting.

- The Amsterdam period before the bankruptcy (1632 - 1658). He produced twenty-five self-portraits in painting and eleven in etching, and he represented himself four times in genre scenes.

- the Amsterdam period after the bankruptcy

(1659 - 1669). This period was a time of great physical

and moral misery for Rembrandt. During this period he

produced eleven self-portraits in painting, one in etching

and two in drawing.

II – The Leiden period (1624 – 1631)

The

historical context *

Part of the seventeen provinces of the Spanish Netherlands with a Protestant majority rose up against ultra-Catholic Spain during the Eighty Years' War from 1568 to 1648. Leiden, the second largest city in Holland and a center of the cloth industry, was besieged by Spanish troops in 1573-74. Leiden was not taken, the siege was lifted on October 3, 1574, but a quarter of its population died of hunger and disease during the siege. In 1581 seven provinces led by Holland proclaimed their independence and took the name of the Republic of the Seven United Provinces of the Netherlands. A truce was signed in Antwerp in 1609 and lasted twelve years until 1621. During the Eighty Years' War (1568 - 1648), there were many land battles between the United Provinces and Spain, but there were also many naval battles between the United Provinces and Spain and Portugal to break their naval hegemony and to take control of the sea routes. Six naval battles pitted the United Provinces against Spain in 1573-1574. In 1588, ships from the United Provinces participated alongside the English fleet in the fight against the Spanish Invincible Armada. Two naval battles pitted the United Provinces against Portugal between 1601 and 1606. Three naval battles opposed the United Provinces to Spain between 1606 and 1615. And finally, ten naval battles opposed the United Provinces to Spain and Portugal between 1621 and 1647. The Eighty Years' war ended with the Treaty of Munster in 1648, when Spain recognized the independence of the United Provinces. After 1648, Spain and Portugal had lost all hegemony over the world's seas.

The Wars of Religion, which led to the sacking of Antwerp in 1576 and its siege in 1585, completed the city's supremacy. The religious intolerance of the Catholics caused the most dynamic elements of the population to emigrate, the scholars, the printers, and the Republic of the Seven United Provinces inherited the industry and commerce of the Southern Netherlands (Belgium). The city of Leiden grew very rapidly, from 15,000 inhabitants in 1573 to 45,000 in 1622. To thank Leiden for its heroic resistance during the siege of 1574, William I of Orange created the University of Leiden in 1575, which became very famous and was attended by the greatest thinkers. In addition to being a major center of the textile industry, Leiden became an important center of printing and publishing after the temporary arrival of Christopher Plantin invited by the University of Leiden and the Elzevier family from Leuven. In 1613, two theologians of the University of Leiden, Jacobus Arminius and Francescus Gomarus, quarreled over the question of predestination. The supporters of Arminius, called the Remonstrants, were convinced of man's effective earthly action on a divine plane. They succeeded in gaining power in the city council of Leiden. In the United Provinces, which were predominantly Calvinist, the two currents coexisted, the remontrants, tolerant but minority Calvinists, and the counter-remontrants, rigorous Calvinists. The Dutch took advantage of the truce to heal their wounds, prepare for war again and settle their religious quarrels. In 1618, the Synod of Dordrecht decided in favor of the counter-remontrants. Governor Maurits immediately took power in Leiden by force and Rembrandt's father, who was a remonstrant, lost his public functions. Although some religious minorities are tolerated, their members are not allowed to hold important positions in society. Johan van Oldenbarneveldt (1547 - 1619), a former collaborator of William I of Orange-Nassau, hero of the siege of Leiden and one of the leaders of the remontrants, was arrested on the orders of Maurice of Nassau, son of William I, then accused of treason and executed in 1619. The famous humanist and jurist Hugo Grotius (1583 - 1645), another leader of the Remonstrants and a former student of the University of Leiden, was arrested. He managed to escape by hiding in a trunk of books and to leave the country.

The plague was endemic throughout the 17th century in the Netherlands, with peaks of activity. For the city of Leiden, the peaks of plague activity were in 1624-25, 1635-36, 1655, 1664. In spite of district containment measures, the plague decimated the city in 1635-36.

If the Dutch society showed a certain tolerance towards religious minorities and thinkers (scholars, philosophers ...), it showed little one towards their way of life. An unusual lifestyle out of the ordinary was very badly lived. We will mention the examples of the beggars in Amsterdam and the painters Torrentius and of course Rembrandt. "In 1613, the municipality of Amsterdam banned all begging and opened two institutions of forced reeducation, the Raphuis for men and the Spinhuis for women" (Renouard de Bussierre S. 1986 see Self-portrait as a beggar). The painter Johannes Symonsz (Jan) van der Beeck (1659 - 1644), called Johannes Torrentius, was a painter from Amsterdam. He was known as one of the best still life painters. He was considered to have a libertine lifestyle, that is, questioning the established dogmas, he was a free thinker. He made the mistake in 1620 of stelling in Haarlem, a city much less tolerant than Amsterdam. In 1627, he was arrested, accused of blasphemy, heresy, atheism, Satanism, being a member of the Rosicrucians and moreover of engraving or painting erotic works. He was tortured, put in solitary lockdown and sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment. All his works were destroyed, only one painting survived him, the Still life with Horse Bridle (1614). In 1629, Charles I, King of England, a great admirer of Torrentius, managed to obtain his release and brought him to England. Unfortunately, Torrentius, traumatized by what had happened to him, was unable to return to painting. He returned to Amsterdam in 1642 where he died in misery in 1644. Rembrandt was brought to justice and in 1658, the whole of Amsterdam's good society took advantage of his bankruptcy to get rid of him.

Rembrandt's

beginnings

Between 1614 and 1620, Rembrandt was a student at the Latin School in Leiden. He learned calligraphy and drawing from a certain Henricus Rievelink (M. Taylor, 2007). In 1620, he enrolled at the University of Leiden without being assiduous because he was only interested in drawing and painting. In 1621 Rembrandt began a three-year apprenticeship with the Leiden painter Jacob van Swanenburgh (1571 - 1638) and worked also with Joris van Schooten (1587 - 1651). He set up a studio in his father's mill. In 1624, he completed his training by working for six months in Amsterdam with Pieter Lastman (1583 - 1633), where he was introduced to Italian painting, of which Lastman was a great connoisseur. He also worked with Jan Pynas (1582 - 1631), a friend of Lastman. Back in Leiden, he founded his first studio at Langebrug 89 probably with his childhood friend Jan Lievens (1607 - 1674). In 1628, Gerrit Doo (1613 - 1675), aged fifteen, became his first student. G. Doo was a very talented young painter who painted a portrait of Rembrandt in his studio in Leiden. Around 1629 Rembrandt acquired a printing press and began a collaboration with the Leiden engraver Jan van Vliet (c.1605 - 1668), which continued for several years after his move to Amsterdam. During his period in Leiden Rembrandt probably had four more students. Rembrandt and Lievens' studio quickly soon became their research laboratory and a hive in which each others' activity stimulated the work of the others. Rembrandt was soon recognized as a very talented young painter. As early as 1628, Aernout van Buchell (1565 - 1641), a humanist from Utrecht, wrote that Rembrandt was a highly prized young painter with a reputation as an "terrible child" and worried about the consequences of too early a success. After painting a canvas, he was advised to present it to an amateur in The Hague, and he took it to him and sold it for 100 guilders. After this first success, the lure of gain encouraged him to work with the utmost diligence. In 1629, Constantijn Huygens (1596 - 1687), a statesman, poet and musician from The Hague, became enthusiastic about the young painter Rembrandt, whose name was already known to wealthy art lovers and collectors.

When a young painter had trained, before setting up a studio, he was supposed to travel to Italy to discover the paintings of the Italian masters. But Rembrandt's favourite models were not Apollo or Venus, but a peasant, a tavern waitress and all the poor people one met on the streets. Rembrandt's true masters were nature and its exceptional dispositions. Rembrandt drew and represented what he saw around him without seeking to embellish it, he was a painter in the most perfect tradition of the Flemish school defined by Pieter Breughel the Elder (c. 1525 - 1569), one of the founders of the Flemish school who said "paint what you see". Rembrandt's world was limited to his studio, which was his research laboratory with his students and collaborators, his family, the Bible and its stories and the neighbourhood in which he walked, observed the lives of his fellow citizens and found subjects to draw. His neighbourhood expanded over time to include the countryside around Amsterdam. Rembrandt was very castaneous and did not travel very far. Although he lived near the port of Amsterdam, he did not draw any of the large sailing ships that travelled the world and made the richness of Amsterdam, only the boats and 'skutjes' (flat-bottomed sailing ships equipped with drifts that were characteristic of Friesland) that he encountered on the canals during his walks. Rembrandt was a hard worker, he did not have a high lifestyle and made no effort to present himself. He was always dressed in his painter's coat, full of ink and paint stains, and he was not embarrassed to rub shoulders with the poor, the tramps... His friend and sponsor Jan Six (1618 - 1700) advised him to make an effort of presentation, without success. Rembrandt loved money and earned a lot of it. Unfortunately for him, he had a great weakness, an addiction, he couldn't stop spending all his money on buying and collecting art.

It was

probably during his six-month stay in Pieter Lastman studio in

Amsterdam that Rembrandt was introduced to etching. In

1625-26, on his return to Leiden, Rembrandt began etching and

printed his first plates in 1626 and 1627. Between circa 1628

and 1631 he developed and perfected his etching technique with

Jan van Vliet. During the period 1628 - 1631, Rembrandt made

about seventy etchings (including twenty-four engraved

self-portraits), i.e. almost a quarter of his output! The

years 1630-31 marked a decisive turning point in Rembrandt's

career as an etcher. It was during this period that he

perfected his etching technique with the Self-portrait with Hat and Ruff and his technique of transferring a drawing to a

copper plate with the etching of Diana Bathing.

The series of self-portraits highlights Rembrandt's extraordinary imagination, as he never drew or painted a subject in the same way twice. Finally, it should be noticed that when Rembrandt drew or painted a self-portrait, he looked at himself in a mirror so the drawing or painting was reversed. Nontheless in the case of all the etchings of self-portraits, the prints are not inverted and Rembrandt appears to us as we would have observed him. Indeed, if he engraved from a preparatory drawing, to keep the spontaneity of his line, he did not invert his drawing when etching, and so the engraved drawing on the plate is also inverted while the print is not, and if he etched his plate by looking at himself in a mirror and not from a preparatory drawing, his engraved self-portrait on the plate was inverted and the resulting print is again a non-reversed self-portrait. Although most of the preparatory drawings have disappeared, there are a few cases showing that the engraving made from a preparatory drawing is not inverted and therefore the print is a non-inverted portrait of Rembrandt. Eventually, some of his engraved self-portraits may have been made in collaboration with J. van Vliet or some of his students, and some are in fact portraits they made.

Rembrandt includes his first

self-portraits in group paintings. Examples include his self-portrait

in The Stoning of St.

Stephen (1625), his self-portrait

in The

Historical Scene (1626), his self-portrait

in Let the

Little Children Come to Me (1627) and his self-portrait

in David

Handing Goliath's Head to Saul (1627). The

painting The

painter in his studio is also worth mentioning,

although it is not a self-portrait. Between 1628 and 1631, he

painted eight self-portraits.

In his first painted

self-portraits, Rembrandt shows us the main features of his

personality in a very natural way. In the Self-portrait

as a Laughing Soldier (circa 1628), he shows us

his playful side, that he had a great sense of humour, that he

liked to party, dress up and was not afraid of self-mockery.

In the Self-portrait

with a Shaded Face (circa 1628), for example, or

in the Self-portrait

with an Open Mouth (circa 1629), Rembrandt paints

part of his face and his eyes in shadow. This unusual manner

shows from Rembrandt a kind of shyness, mischief, and even

provocation. He seems to be saying: "You can't see me, but

I can see you, indeed!". The paintings Self-portrait

with a Feathered Beret (circa 1629) and Self-portrait

in Oriental Costume with a Dog (circa 1631) shows

that Rembrandt disguises himself. In the course of his life,

he retained this manner, the mischief and provocation in some

of his self-portraits. However, in his first engraved

self-portraits from the Leiden period, a large part of his

face often disappears in the overly intense shadows, but this

is due to his lack of mastery while he discovered etching. He

did not yet know how to make gradations or details in shadows

or dark areas.

The main characteristic of Rembrandt's drawings is

the freedom of the line. The engraving technique that allows

this freedom of line to be maintained is the etching one.

Nowadays, to make an etching, the engraver covers a metal

plate (copper or zinc, Rembrandt used copper) with a varnish.

When the varnish is dry, the engraver draws on the plate with

a very thin metal needle which removes the varnish. When the

drawing is finished, he protects the back of the plate with

varnish and immerses it in acid which will attack the metal

where the varnish has been removed. When the acid attack is

finished, he removes the varnish and the lines of the drawing

appear in the metal. The engraver covers the plate with ink

and then wipes the surface of the plate so that the ink

remains only in the deeps of the lines. The engraver puts the

plate on the press, covers it with wet paper and passes it

through the press, which produces a strong pressure. The

pressure from the press compresses the paper into the line of

the plate and then the ink settles on the paper.

Before presenting the Leiden period, we will introduce the etching technique at the time Rembrandt started to engrave. To illustrate the Leiden period, we will present The Uncovered Head Self-Portraits, followed by The Covered Head Self-Portraits and The Self-Portraits of Expression of Sentiment or Emotion, and finally The Self-Portrait with Hat and Ruffle, which enabled Rembrandt to develop his etching technique. The exceptional progress Rembrandt made in the three years 1628, 1629 and 1630 can be seen in the etchings Self-portrait with Flying Hair (circa 1631), Self-portrait with Thick Fur Hat (1631), Self-portrait with Wide Eyes (circa 1630) and finally the Self-portrait with Hat and Ruff (1631). Finally, we will discuss the importance of Rembrandt's collaboration with J. van Vliet and Rembrandt's contribution to the etching technique.

The

etching technique before Rembrandt

The etching technique was developed by Arab goldsmiths in

Spain and Syria in Damascus. The metal is covered with a more

or less transparent varnish that remains soft, called soft

varnish or vernis mol. The use of a soft varnish makes

the work very delicate, because if you put your hand or

fingers on the varnish it sticks to your finger and when you

pour acid on the plate, the fingerprint is engraved. The acid

used to attack the metal was nitric acid, formerly called aqua

fortis. Nowadays, iron perchloride is used to etch

copper, which is far less toxic than nitric acid.

Masso Finiguerra (1426 -

1464), an Italian goldsmith and engraver, wanted to check his

Triumph

and Coronation of the Virgin, taken up to Heaven and

surrounded by Angels (1452), before filling in the

lines with niello, he wanted to try out what the engraved

figures would look like on a sheet of damp paper by filling in

the lines with smoke from a candle. The paper faithfully

reproduced the subject traced on the metal. This technique,

which consists of filling the engraved deeps on the metal with

ink, is called intaglio. Niello is a black silver sulphide

that is embedded in engravings of precious metal. Andrea

Mantegna (1431 - 1506), an Italian painter and engraver, is,

along with Masso Finiguerra, considered the inventor of

copperplate engraving (chalcography) in Italy. He engraved

with a burin (see for example The

Descent into Limbo of 1475). Copper engraving

spread to Italy, Burgundy, Flanders and along the Rhine

valley.

Daniel Hopfer (c.1470 - 1536), a German armourer and engraver, was the first to use the etching technique to print pictures (see for example Three old Women beating the Devil). Metal plate engraving developed in the early 16th century (1513) in Switzerland with Urs Graff (1485 - 1527), in Germany with Albrecht Dürer (1471 - 1528) and then in Italy, from 1530, with Francesco Mazzola (1503 - 1540). It very quickly became one of the favourite technique of engraving painters. At the beginning of the 17th century, the Dutch engraver Simon Frissius (c.1570-75 - c.1628-29) (see for example Landscape) and the Swiss engraver Matthäus Merian, known as the Elder (1593 - 1650), who began using etching around 1610-15, are considered to be the first great etchers and obtained prints that can be compared to those obtained by engraving with a burin (A. Bosse 1645).

To reproduce a drawing, painting or landscape in engraving, at first, one must draw it in reverse of the drawing, painting or landscape. The engraver then transfers the reversed drawing to the plate so that the print on the paper corresponds to the original drawing. To do this, it is necessary to make a reproduction or counterprint of the inverted drawing to be engraved on the varnish of the plate to obtain a non-inverted print. But Rembrandt, who wanted to keep the freedom of the line and the spontaneity of a first drawing, never made the same drawing twice when studying a subject or a theme and drew directly on the plate without inverting the drawing when he engraved. His prints then appear inverted, which did not bother him at all. Nevertheless, he sometimes transferred a drawing to a plate to make an etching, which was like copying his drawing onto a plate. He initiated himself into the transfer technique with the very crude etching Saint Paul in Meditation (1629) before perfecting his transfer technique with the etching Diana Bathing (1630), which we will discuss in detail in the chapter on Scenes of Intimate Life.

1) in 1616-17, the use of a transparent hard varnish used by the luthiers of Florence and Venice, made etching technique much easier, as one can touch the varnish or put something on it without damaging it. After varnishing the plate with the hard varnish, it must be dried by heating the plate. This varnish was quickly adopted by many painters and engravers of the 17th century and its was used until the beginning of the 18th century (A. Bosse, 1645, 1743 edition).

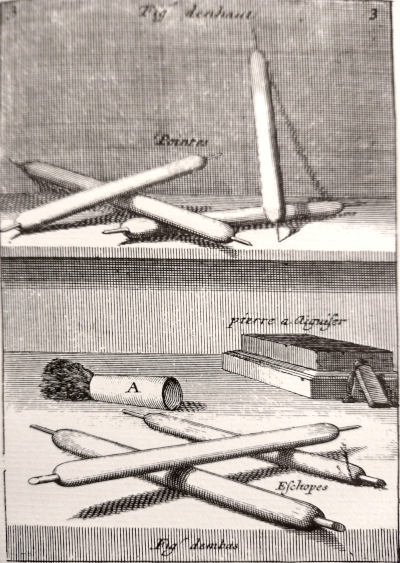

2) the use of the “échoppe” or chisel, a tool similar to the burin, borrowed from the goldsmiths, which allows to make broad and fine strokes. Unlike the burin which has a square, rectangular or diamond-shaped section and is bevelled, the chisel has a round section and is also bevelled.

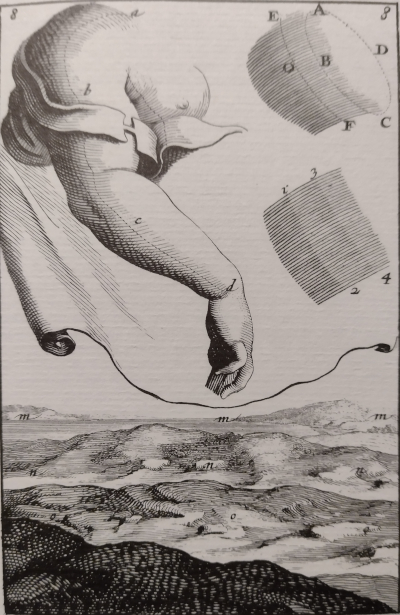

Examples of needles (top) and “échoppes” or chisels (bottom)

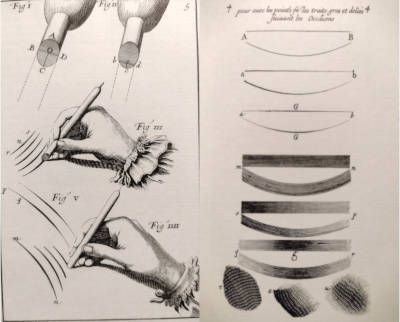

Examples of broad and fine strokes obtained with “échoppes” or chisels

3) the multiple acid attack technique. In general, it consists of making three successive attacks to give three different intensities to the lines and create gradations and/or obtain the impression of volume. The longer the plate is left in the acid, the deeper the attack. First, a relatively short attack is carried out, then the plate is washed with water, the varnish is removed from the area to be protected with a soft willow charcoal soaked in water, taking care not to scratch the plate, then the area from which the varnish has been removed is covered to protect it from the acid with a tallow-oil mixture applied with a brush (tallow is the fat of herbivorous animals, which is collected by melting; this melted fat was formerly used to make candles, ointments, soaps and lubricants). Acid is poured onto the plate again and a second, deeper attack is obtained. Finally, the procedure is repeated a third time (see Figure).

Etching obtained using the multiple acid attack technique

The use of a transparent varnish allows another

way, much simpler than the technique of multiple attacks, to

obtain lines of different intensity to give volume. Three

different attacks are made with different times, combined with

the use of different size needles. In the first stage, the

less intense lines are drawn very lightly, corresponding to

the areas generally furthest from the landscape and/or to

construction lines, then a fairly short acid attack is carried

out and finally the varnish is removed from the whole plate

and a print may be made to visualize this first stage. After

removing the grease and re-varnishing the plate, the lines

corresponding to the intermediate zones are drawn more heavily

and a second, longer acid attack is made. The varnish is

removed again and a print may be made to visualize the two

first stages. Finally, the grease is removed from the plate

and it is varnished again to draw once more and make a third

acid attack which will be the longest and will produce the

darkest lines often corresponding to the foreground and shaded

areas of the landscape.

Jacques Callot was a very

famous etcher.

When Rembrandt started etching in 1625, there were no standard products or methods for etching and each engraver had his own method and products. The practice of engraving in the 17th century was very complex and work intensive. There were no ready-made copper plates for engraving. One had to know how to choose the right copper, and then have the plate made and polished by a boilermaker. If the engraver had to polish a plate or part of a plate, he would first polish the plate with sandstone, then with pumice, then with a soft whetstone, then with willow charcoal and finally he would finish off the last scratches with a burnisher. Before varnishing the plate, it had to be cleaned and the grease removed by rubbing it either with stale breadcrumbs or with chalk powder (nowadays we use Meudon white) and then wiped with a clean cloth (if the grease on the plate is not well removed, the varnish will not adhere well and the acid will penetrate under the varnish). To engrave a plate covered with soft varnish, the plate was placed on a small table easel to avoid touching the varnish and was engraved with the needle as one would draw or paint on a table easel. When the drawing had been engraved on the varnish, the plate was attacked with acid. Before attacking the plate with acid, the back of the plate and its edges were protected with the tallow-oil mixture. There were two ways of attacking the plate with acid, both used by Rembrandt. Either the acid was poured eight to ten times onto the plate, which was placed on a sloping surface (Figure), or the plate was edged with wax (a small wax rim was built around the edge of the plate), and then, after placing the plate horizontally on a table, the acid was poured onto the plate. Nowadays, after protecting the back of the plate, it is immersed in a tank containing acid. When the acid attack was finished, to remove the varnish from the plate, the plate was heated to soften the varnish and wiped with a cloth soaked in olive oil.

How to pour the acid on the plate

In his early years Rembrandt most probably used a soft varnish more or less transparent. It may be possible, but we do not know, that he started to use a transparent hard varnish (the one used by violin makers, carpenters or shipwrights) after the beginning of his collaboration with Jan van Vliet around 1629. The use of a transparent hard varnish makes etching much easier. As Rembrandt drew on the plate without inverting his drawing, he did not have to trace the drawing on the varnish of the plate and could therefore draw on the varnish without having to blacken or withen it. As the varnish was transparent, he could easily make three different acid attack with different times, which he combined with the use of needles of different sizes to give three different intensities to the lines and thus create an impression of volume (see for example the View of Amsterdam). He could repeat the different steps or acid attacks and/or perform them in a different order. This technique is much easier to use than the multiple acid attack technique of Jacques Callot. Rembrandt used weak (or diluted) nitric acid to better control the acid attack.

View of Amsterdam (1641), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}

Self-portraits with

uncovered head

Self-Portrait Leaning Forward

Self-Portrait Listening Leaning Forward (etching, circa 1628), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}. It is very interesting to compare this etching with the Self-Portrait Leaning Forward (circa 1628). In this print, there are two very different levels of intensity in the lines and hatchings. Rembrandt uses more or less thin needles to remove the varnish and makes two acid attacks of varying length time to obtain more or less fine or intense lines.

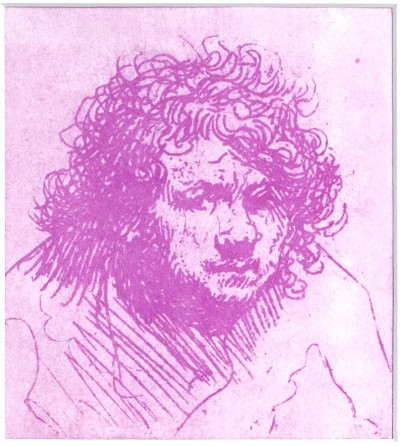

Self-Portrait with Disheveled Hair (drawing, circa

1629, Benesch, B 54, Schatborn & Hinterding,

D 628), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}. Drawing made with brush and

pen. This drawing will be followed by the etching Barehead

Self-Portrait (circa 1629) and the painting Self-Portrait

with Gorgerin (1629). Note the three different

ways of treating the same subject, a method characteristic of

Rembrandt's work to keep the same freshness each time and

never produce the same work twice, even if the technique is

different. This shows Rembrandt's exceptional faculties of

inventiveness and memory.

The self-portraits painted with the head uncovered are: Self-Portrait

with

Shaded Face (circa 1628), Self-Portrait

with Gorgerin (circa 1629) and Self-Portrait

(circa 1629).

Self-portraits with

covered head

Self-portrait with a Fur Cap (etching, circa 1629), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}. Rembrandt does not yet master gradients or details in shadows or dark areas.

Studies

Self-portrait with Hat forward

Self-portrait with Hat forward (etching, circa 1630), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}.

Self-portrait with Fur Hat (etching, circa

1630), {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam}.

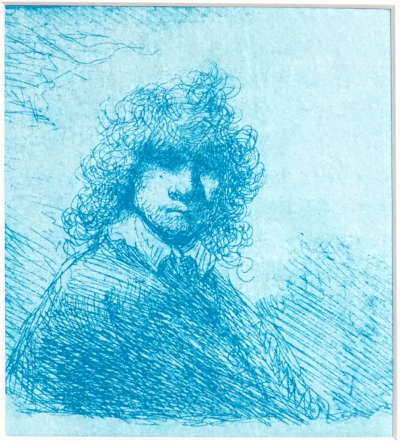

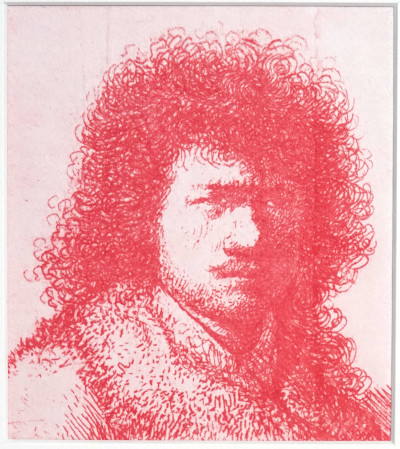

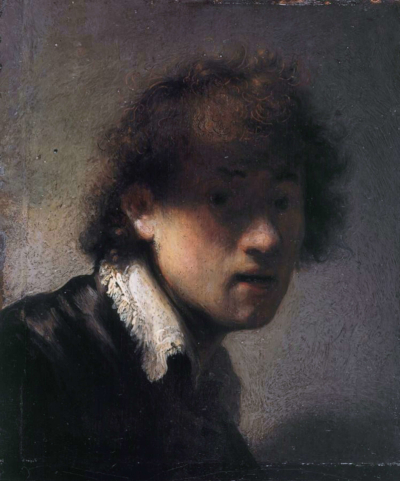

The self-portraits painted with the head covered are: Self-portrait with a Feathered Beret (c.1629), Self-portrait (c.1630) and Self-portrait in Oriental Costume with a Dog (c.1631). It is particularly interesting to compare his Self-portrait of c.1630 with the Portrait executed in 1628 by Jan Lievens {private collection}, as the portrait by Jan Lievens shows Rembrandt's face not inverted.

Self-portraits of emotion

expression

Sel-portrait with Open Mouth -

(c. 1629a), {Alte

Pinakothek, Minich}

Smiling Self-Portrait with Hat

Rembrandt trained to express emotions and feelings

by working on self-portraits. Later, one of his great

specialties was the expression of different emotions and

feelings when representing groups of figures, animals and even

landscapes. We are going to present two examples of etchings

made after the Leiden period, but which illustrate this

exceptional faculty of Rembrandt and characteristic of the

Baroque period.

Development of the

etching technique

Self-portrait with Hat and Ruff

(1631)

It was while making this self-portrait that

Rembrandt mastered his etching technique. The different steps

of his work make it possible to understand his working method,

as we will see in the following illustrations. There are

fifteen different engraved states of this self-portrait. We

will not present them all, we will present nine of the

different engraved steps and three drawn studies, which

highlight the enormous amount of work, delicacy and virtuosity

that he had to produce for the realization of this

self-portrait. To make this etching, Rembrandt uses a

transparent varnish and this allows him to make several

successive etching attacks, attacks which he prepares with

more or less fine pits to remove the varnish and acid attacks

longer or shorter to obtain more or less fine lines. If

necessary, he erases with a burnisher the part of the etching

he wants to rework and finally he reinforces certain shadows

with a burin and/or drypoint.

This self-portrait shows that if Rembrandt groped for several years to master the art of etching, his progress was dazzling during the year 1630-1631, after his collaboration with the engraver Jan van Vliet.

Self-portrait

with Hat and Ruff

(drawing, Benesch, B 57, Schatborn &

Hinterding,

E 208a ), { British

Museum, London}.

First study drawn for his self-portrait. Using the print

from the first stage, Rembrandt figures and draws the

continuation of the etching. This study is drawn with a

black chalk. AET 24 means "Aetatis suae 24", that

is to say "At the age of 24". The drawing being

made in 1631, this would indicate that it was made at the

beginning of the year 1631 before Rembrandt's birthday on

July 15.

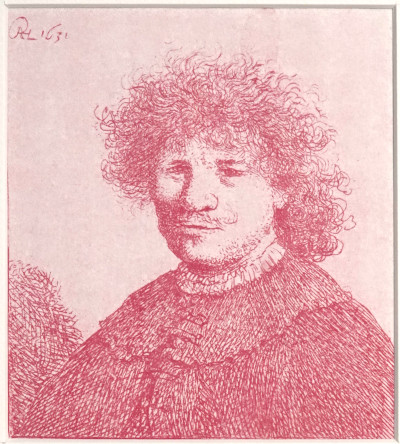

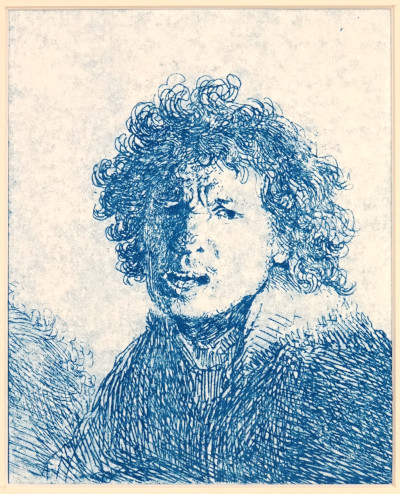

Self-portrait with Hat and Ruff (etching), { Bibliothèque nationale, Paris}. In this step, Rembrandt built the character and the general shape of his coat without working on either the decoration of the habit or the background of the plate. He is happy enough with this step to sign it in the top left. Signature which will disappear in the following steps and will not be the final signature of the plate.

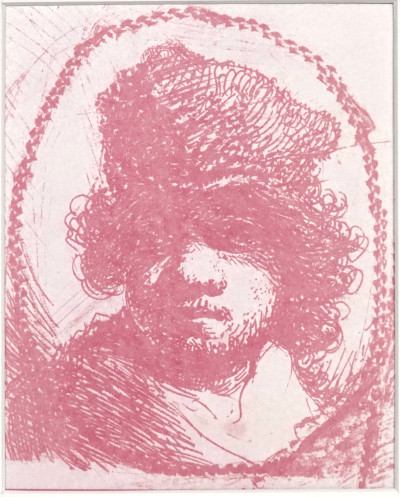

Self-portrait with Hat and Ruff (etching), {Bibliothèque nationale, Paris}. In this step, to highlight the

volume, Rembrandt works the bottom of the plate which

gives depth and highlighting.

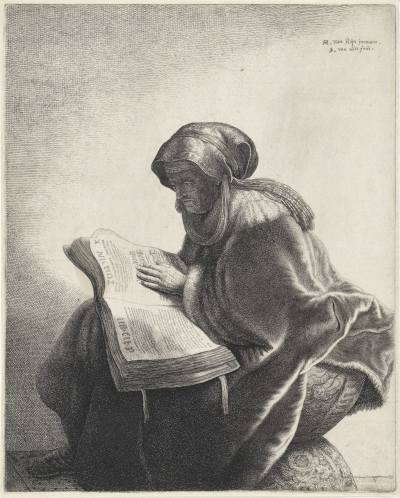

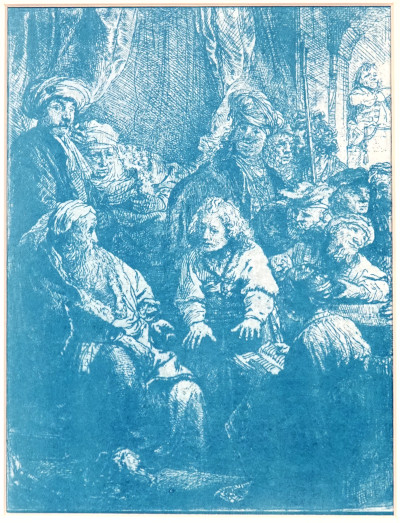

By 1631, when Rembrandt developped his etching technique with his Self-Portrait with Hat and Ruff, Jan van Vliet was able to engrave with the same level of virtuosity as shown in his etchings Loth and his Daughters, The Baptism of the Eunuch and Anna the Prophetess.

Lot and his Daughters (c. 1631), {Rijksmuseum Amsterdam}

Lot and his daughters (c. 1631), etching by J. van Vliet reproducing the drawing Lot and his daughters (c. 1631) by Rembrandt or his workshop.

Rembrandt never liked

to draw the same thing twice and he engraved

without inverting his drawing to keep the

spontaneity of the line. It was probably Jan van

Vliet who introduced him to the technique of

transferring a drawing onto the varnished plate

before engraving it when making the etching Diana

Bathing

(technique which will be explained in the chapter

of the scenes of intimate life during the study of

the etching Diana

Bathing).

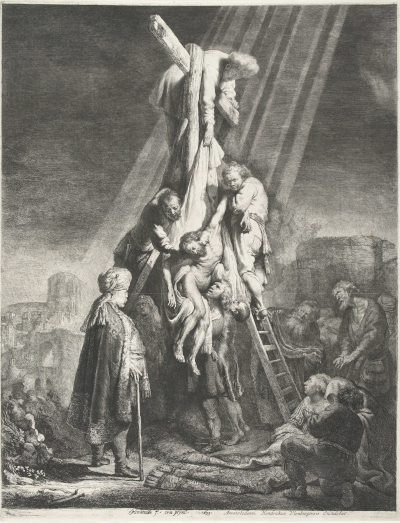

Jan van Vliet worked

with Rembrandt producing etchings, for example The

Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (c. 1631) and his two largest plates The

Great Descent from the Cross (c. 1633) and Christ before Pilate (c. 1635).

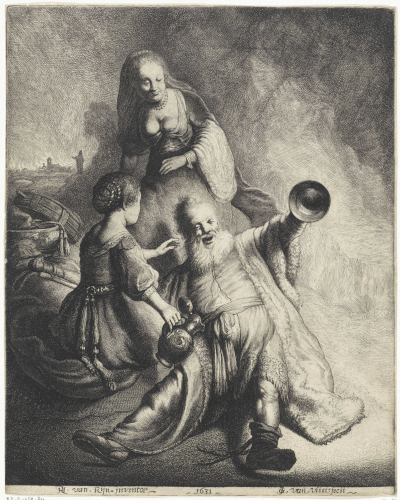

Jan van Vliet also played an important role in introducing and distributing Rembrandt's work by etching it (etching or engraving was the only way to reproduce drawings or paintings in the 17th century). Examples include Lot and his Daugthers (c. 1631), Anna the Prophetess (c. 1631-34),

Anna the Prophetess (c. 1631-34), {Rijksmuseum Amsterdam}

Anna the Prophetess (c. 1631-34), etching by J. van Vliet reproducing the painting Anna the Prophetess by Rembrandt (c. 1631).

Anna the

Prophetess (c. 1631), {Rijksmuseum

Amsterdam}

and Rembrandt's Self-Portrait (c. 1634) which is the

copy of the 1628 self-portrait and

the copy

from 1634 of Self-Portrait

with Hat and Ruff

(c. 1631).

Hercules Segers (Haarlem c. 1589-90, Amsterdam c. 1637-38) was a highly original painter and engraver who was one of the greatest experimenters in the field of etching. He had a difficult life, went bankrupt and met a tragic end. At the end of his life he started to drink and is said to have died as a result of a fall down on the stairs. Samuel van Hoogstraten, in his "Introduction to the Great School of Painting", presents him as a lonely, poor and misunderstood genius.

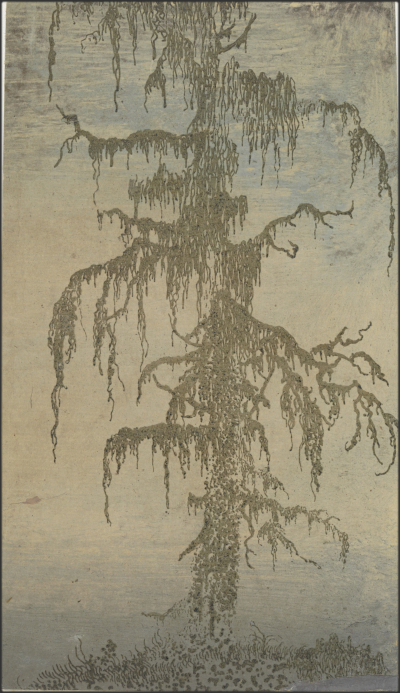

Hercules Segers is probably the most singular Dutch painter-engraver of the Golden Age, see for example: The Moss Tree, etching and watercolour {Rijksmuseum Amsterdam}, the paintings "River valley", {Rijksmuseum Amsterdam} and The Mountain Landscape, {Bredius Museum, Den Haag}.

Landscape with a Fir Branch (c. 1626-30), {Rijksmuseum Amsterdam}

Although Rembrandt and Hercules Segers did not live in Amsterdam at the same time, Rembrandt was familiar with Segers' work and considered him as his master. He admired him for his exceptional research and technique in etching, his originality, his creativity, the independence and freedom of his style. Rembrandt owned eight paintings, several prints of his etchings and even a plate Tobias and the Angel by Hercules Segers.

H. Segers influenced Rembrandt in painting and etching:

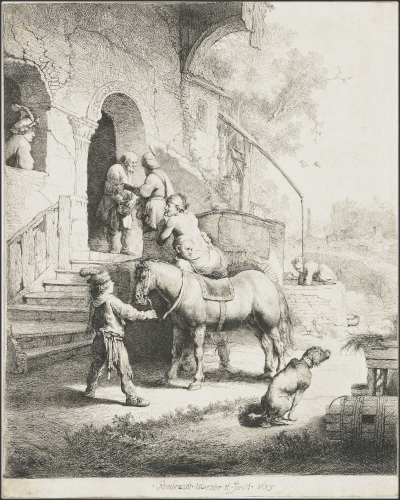

- 1) Painting: the skies, lights and atmospheres of Segers' landscapes (e.g. The Mountain Landscape {Galerie Uffizi, Florence}, owned and reworked by Rembrandt or The River in the Valley {Maurithuis, Den Haag}, inspired Rembrandt in his landscape paintings: Stormy Landscape (1638) {Herzog Anton Ulrich museum, Brunswick}, The Stone Bridge (1638) {Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam} and The Good Samaritan 1638) {Czartoryski museum, Karkóv}.

- 2a) Etching: Before Rembrandt, the ultimate goal of the etching technique was to achieve a result comparable to burin-engraving technique (A. Bosse 1645). Nevertheless Rembrandt thought the interest in using etching is to obtain all the shades that painting allows, to be able to make real etched pictures with gradations and details in the shadows and dark areas. Very soon after the development of his etching technique (1631), Rembrandt's etchings became comparable to paintings that depict and describe scenes of life, for example: The Ratcatcher (1632), The Great Raising of Lazarus (1632), The Good Samaritan (1633), The Great Descent from the Cross (1633). These etchings allowed Rembrandt to give free rein to his fantasy and imagination. If Rembrandt's prints become comparable to paintings, unlike H. Segers, Rembrandt achieved this result without adding colours to the paper before or after the print.

The Good Samaritan (1633) etching. Again Rembrandt does not simply copy the painting and although it is a biblical scene, he sets it in the countryside and adds a dog relieving itself in the foreground. This is characteristic of Rembrandt's facetious and provocative side. This theme will be taken on in painting.

Few years latter, Rembrandt reproduced the theme of the Good Samaritan in a landscape directly inspired by the landscapes of Hercules Segers.

- 2b) While

most etchers gave their plates to a printer

for printing, Rembrandt, like H. Segers,

made his own prints. Rembrandt repeatedly

tried prints with different coloured inks

and took great care in wiping the ink, which

accentuates contrasts (dark areas are wiped

less than light or white areas), creating

different atmospheres and finally in

choosing paper for the print. Rembrandt

preferred to make prints on papers that came

from China or Japan (see further details in

the next section Rembrandt

and the Etching Technique).

Rembrandt reworked Hercules

Seghers's plate Tobias and the Angel (1630-33)

into The Flight into Egypt (1653),

keeping the landscape.

The Flight into Egypt (1653). This print differs from the previous one in that the ink is wiped off less and the choice of paper is different. The very different atmospheres of these two prints are noticeable.

- Rowlands J., 1979, Hercules Segers, George Braziller, New York

- Sloten van L. & de Jongh E., 2016, « Under the Spell of Hercules Segers, Rembrandt and the moderns », W Books, Zwolle

Rembrandt

and the etching technique

Printmaker's workshop (A. Bosse c. 1642)

The Hundred Guilders Coin (c. 1648), {Rijksmuseum Amsterdam}

The

drypoint technique uses a

steel needle that is used to

engrave lines into the metal

plate. Two examples of etching

completed with drypoint are The

Death of the Virgin (c.

1639) and Christ

Crucified Between Two

Thieves (c.

1641). Rembrandt uses drypoint

to create the most intense

blacks. An etching completed

with drypoint allows to make

about fifteen prints only

because the pressure of the

press quickly crushes light

copper beads. From 1648 he

used increasingly drypoint in

his etchings, and even made

some engravings only with

drypoint, which confused his

admirers and collectors.

Examples include the

landscapes The

Clump of Trees (c.

1652), The

Canal (c.

1652), and the engraving Ecce

Homo (c.

1655) of which only eight

copies were printed.

The burin

engraving uses a burin that is

used to engrave lines into the

metal plate. Two examples of

etching completed with a burin

are The

Great Descent from the

Cross (c.

1633) and Christ

before Pilate (c.

1635). An etching completed

with a burin makes it possible

to print between one hundred

and one hundred and fifty of

them.

To work on his plates, Rembrandt could use a print on which he drew, see the examples of Self-portrait with Hat and Ruff presented in the section: The Development of the Etching Technique, and the Portrait of Rembrandt's Mother.

In the case of very complicated plates, Rembrandt would make a counterproof on which he would draw. The counterproof is an inverted print and is similar to the copperplate etching. Once he had perfected his drawing on the counterproof, he only had to redraw it on the varnish of the plate to obtain the new state of the plate. There are very few examples of this type. This is the case with the counterproof of the first state of the plate The Gold Weigher {The Baltimore Museum of Art}.

If he considered it necessary, Rembrandt could erase part of the plate with a burnisher and scraper. He used the scraper part (a triangle shape with sharp edges) which made it possible to remove the metal beads and scraped the copper around the lines, then the burnisher part (rounded and smooth) crushed the copper and erased the engraved lines that remain and the scratches made by the scraper. This operation is very long, hard and touchy because the plates used by Rembrandt were thin. He could change a large part of the plate to rework it and strongly modify the processing. Examples include Self-Portrait with Hat and Collar (realisation of embroidery) (c. 1631), then much later the major shifts, The Flight into Egypt (c. 1653) using a Hercules Seghers plate from c. 1630-33, The Three Crosses (c. 1653), first state and fourth state and Christ Presented in the Temple (c. 1655), third state and seventh state. Erasing part of a plate with a burnisher represents considerable work and shows that for Rembrandt only counts the result he wanted to obtain, regardless of the amount of work he had to provide to achieve the goal he had set himself.

Finally, while printing,

Rembrandt took great care

with the wiping of the ink,

which accentuates the

contrasts (the dark areas

being wiped less than the

light or white areas) and

finally with the choice of

paper.

For

Rembrandt, there is no

predefined rule, the result

is the only thing that

counts. He

adapts the rules and the

technique he uses to the

subject he is dealing with

and according to the result

he wants to obtain.

After his

bankruptcy, the seizure of his

press and his move in 1660, he

could not reinstall an etching

workshop as well equipped and

produced only two etchings.

Unlike Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt never engraved on wood, most probably because wood engraving does not offer the freedom of line that etching allows.

Ingredients used

Important improvements were made over the centuries when alchemists used the exudates secreted by certain plants (an exudate is the substance that flows out of the plant, for example pine resin) and distilled them. The use of resins as well as distillation are known since antiquity. Pliny the Elder (23, 79) reports that liquid pitch was extracted by distillation from the resin of the cembro pine or the spruce as well as from oriental trees such as the terebinth, the lentisk, the cypress. This liquid pitch was used in Egypt for the mummification of bodies. Liquid pitch can be reduced by fire and coagulated with vinegar, and was then used to waterproof amphorae. The Greeks caulked ships with pitch mixed with wax and also used distillation to obtain liquors. The first alembic is described in the 4th century (alembic of Zosin, Greek alchemist), during the following centuries distillation is used to purify and obtain new products, ethyl alcohol (called "eau de vie" or "eau ardente" in the Middle Ages), essential oils (also called vegetable essences), esters used in perfumery... The distillation of petroleum is known since the 7th century. In 1500, the German alchemist Jerome Brunschwig (c. 1450, 1512) published the first treatise on distillation.

Among the exudates used are :

- gum arabic from acacia trees, which has been used since prehistoric times as a binder for water-based paints (cave paintings, then gouache and watercolor),

- the vegetable resins obtained essentially from certain conifers. Their distillation produces essential oils as well as a solid or a very viscous residue.

Units used in this section are :

- La Pinte de Paris : ≈ 0.952 litre

- La Livre de Paris : ≈ 490 g

- Le Quarteron = 1/4 de Livre ≈ 123 g

- L'Once

= 1/16 de Livre ≈

31 g

For the manufacture of:

- 1)

aquafortis

(nitric acid),

which is used to

attack copper

plates, one

mixed:

white vinegar, ammonium chloride, sea salt and verdigris also called copper green (A. Bosse 1645). This mixture can be used to etch with hard or soft varnish

- How

to make it:

Take 3 Pintes

of white vinegar, 6 Onces

of ammonia salt, 6 Onces

of common salt and 4 Onces

of copper green. After

pounding the solids

fine, put the whole into

a pot and bring the

mixture to the boil and

stir the whole. After

bringing to the boil the

mixture two or three

times, the aquafortis is

obtained, which is left

to cool and rest for a

day or two before being

used. If you want to

moderate it, add a glass

or two of the white

vinegar used to make it.

- There was another kind of aquafortis called "eau de départ" which was used to separate gold from silver and copper. It was sold in refineries and was made from vitriol (iron sulphate), saltpetre, etc. It could only be used on soft varnish because it dissolved the hard varnish.

- 2) a

mixture of tallow and oil

to cover the areas of the

plates that the acid should

not attack:

Olive oil which prevents the tallow from freezing as soon as it cools.

Tallow, which is obtained from the fat of herbivorous animals (sheep or beef), and is collected by melting the fat. Tallow was used to make tallow candles, candles, ointments, soaps and lubricants (in the wooden mechanisms of mills for example). - How to make it : Candle tallow is mixed with hot oil. The tallow melts in the oil. Enough oil must be added to the mixture so that it remains liquid when it cools.

- 3) the transparent hard varnish used by Jacques Callot, you need : Clear, fat linseed oil (oil used by painters).

- How to make it: Heat one Quarteron of linseed oil and add one Quarteron of pulverized tear mastic. The whole is mixed until the mastic is well melted. The whole mass is then passed through a clean, thin cloth into a glass bottle, which is well sealed to preserve the varnish.

- J. Callot's hard varnish can be diluted with turpentine oil. It is different from the thin varnishes used in oil painting because it contains linseed oil but can also be used as a medium in oil painting. Turpentine resin was produced in ancient times from the turpentine tree, the distillation of which provides turpentine oil and rosin, also called "arcanson" in Gascon. Variants of turpentine resin were produced from other resinous trees (different varieties of pine (pine resin), spruce, larch, fir).

Pulverized mastic in tears. Mastic resin is derived from the Pistacia lentisque tree (a Mediterranean shrub called Pistacia lentiscus or the mastic tree). It is used to make the hard transparent varnish used by J. Callot, but also soft varnishes for etching, and oil-resin mediums and varnishes for oil painting. Mastic resin was the favorite resin of P. P. Rubens. The variety khia or chia, from the island of Chios in Greece, is the most famous since antiquity.

a) Turpentine oil is used as a solvent to make the hard varnish used by J. Callot and some soft varnishes in etching, and mediums and varnishes in oil painting.

b) Rosin, also known as white pitch, has been known since antiquity. It is used in etching to make certain soft varnishes, and in powder form to make aquatints.

- 4) soft varnishes. There are many recipes for making soft varnishes (see the 1743 edition of A. Bosse's book). We will propose one of them:

- Jacques Callot's soft varnish. To make this varnish, you need : Clean, white virgin wax. Wax has long referred to the wax secreted by bees. Wax can also be obtained from spermaceti which occurs in large amounts in the head oil of the sperm whale, oil from the fish "orange roughy" and oil from certain plants (mainly jojoba). In engraving, it is used to make a small wax rim around the edge of the plate and then after placing the plate horizontally on a table, the acid was poured onto the plate, and also to make soft varnishes, in painting it is used to make matte varnishes.

- How to make it: Take half a Quarteron of virgin wax, half a Quarteron of amber or half a Quarteron of calcined spalt (calcined bitumen), half a Quarteron of mastic if working in summer because it hardens the varnish, or only an Once of mastic if working in winter, an Once of resin pitch or an Once of shoemaker's pitch and half an Once of turpentine resine. When all the materials are ready, the wax is melted by heating it and the pitches and then the powders are added little by little, stirring the mixture. When the mixture is well melted and homogeneous, it is poured into clear, cold water and kneaded into balls which are kept away from dust.

Amber or calcined spalt (calcined bitumen).

a) Amber is a fossil resin secreted millions of years ago by conifers or flowering plants. It comes in different colours. Amber is used in engraving to make soft varnishes, and in oil painting to make mediums and varnishes (amber was prized by Salvador Dali to make glazes). Amber has been known since prehistoric times (Paleolithic: amber found in Altamira cave) for the manufacture of jewellery (Halistattien, between 1200 and 500 BC).

b) Spalt is a stone used by smelters to melt metals. But it is the name used by painters and engravers to designate asphalt or bitumen (from Judea). Bitumen exists naturally as a residue of ancient oil deposits from which the lighter elements have been removed by evaporation over time by a kind of natural distillation. Bitumen has been known and used since prehistoric times as a waterproofing material for sealing clay bricks, for making tools or for caulking ships. Bitumen is used in engraving for the production of soft varnishes but also for making aquatints when it is reduced to powder.

Mastic (see the manufacture of hard varnish used by J. Callot).

Resin pitch (old spelling: "poix raisine") or shoemaker's pitch. Pitch is obtained mainly by distillation of the raw resin of the pine tree and is used in the constitution of certain soft varnishes. It is a sticky, viscous and flammable material based on resins and vegetable tars, it is mainly used to ensure the waterproofing of various assemblies. There are many varieties of pitch depending on how it is prepared and the type of tree from which the resin is extracted. Pitch has been known and used since antiquity.

a) Resin pitch is obtained by emulsifying the residue of the distillation of turpentine (rosin) with water (if instead of removing the rosin from the alembic, it is strongly stirred with water, it loses its transparency: it is then called yellow resin or resin pitch).

b) Shoemaker's pitch which is black pitch is obtained by distillation of the resin of certain resinous trees or birch and then by slow combustion of the resinous debris. There it separates into two parts, one liquid called pitch oil, the other more solid is black pitch.

c) White pitch is the rosin obtained by distillation of turpentine resin.

d) Burgundy pitch or Vosges pitch is obtained by distillation of spruce resin.

e) Natural pitch is produced by distillation of larch resin.

Turpentine resine

The soft varnish of J. Callot can be diluted with turpentine oil (see the manufacture of the hard varnish of J. Callot).

- For water-based

paintings,

gouache or watercolor,

the medium used is gum

arabic to which honey

is added ...

The use of gum arabic is known since prehistoric times (cave paintings). - For oil

paintings, in

addition to the

mixture of oil (e.g.

poppy seed oil or

linseed oil) and

pigments (the mixture

of oil and pigments

forms a coloured

paste), resins

are generally used to

make the medium, which

is the binder for the

coloured paste, but egg

white

can also be used. The medium allows to

adjust the properties

of the paste, its

dryness, its

transparency, its

surface appearance,

matte or glossy, it

promotes the

realization of

impastos or glazes.

There are different

types of medium

depending on the

effect you want to

obtain in painting

(impasto, glaze ...).

Mediums based on beeswax

are used since ancient

times. Resin-based

mediums or egg

white

mediums have been used

since the Renaissance.

Oil-resin

mediums are composed

of a natural resin (amber,

mastic,

copal

...), an oil

generally cooked and a

solvent (turpentine

oil

...).

The copal is a semi-fossil resin, close to amber, but generally clearer and is younger than amber. It is generally soluble in alcohol, which is not the case of amber. Copal is used for the manufacture of mediums and varnishes in oil painting.

- The varnish

must be transparent

and consists of:

1a) either a soft natural resin (mastic) which gives a thin varnish,

1b) or a hard natural resin (amber or copal) which gives a hard varnish, - 2) a solvent which dilutes the varnish and modifies its consistency: turpentine oil or alcohol (ethanol) obtained by distillation,

- 3) a possible matting agent (beeswax) which makes the varnish matt.

- Bosse A. (1645), Traité des manières de graver en taille douce (75 pages)

- Bosse A. (1645, Edition de 1743), Traité des manières de graver en taille douce, édition revue, corrigée & augmentée du double (186 pages)